- Shop Talk

- Tim Hussey

- The Biggest Loser

- Palmetto Pointe

- Found Footage Festival

- The Greater Park Circle Film Society

- Nicholas Sparks

- Michael Jackson Movies

- The Botany of Desire

- The Spiderwick Chronicles

- Persepolis

- Rambo

- The Orphanage

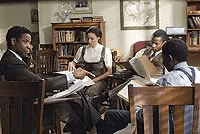

- The Great Debaters

- The Merkin Man

- The Guestworker

- The Projectionist

- America: Freedom to Fascism

- Gryphonpix Entertainment

Shop Talk turns into a surprising hit for C2

by Nick Smith February 17, 2010

Shop Talk, the Comcast C2 chat show, has become a local phenomenon since it began just over a year ago.

The format is simple: Charleston-based hosts PC (real name Paul Curry) and bespectacled, hand-rubbing ex-rapper Sman the Man (Ivan Heyward) chat while their interviewee sits in a barber chair. Everybody faces the camera. It’s just like a few friends yakking in a barber shop, except this time the conversation is shared with the rest of Charleston. Shop Talk covers relationship issues, the black community, and entertaining everyday matters.

At their studio in North Charleston, the two presenters react quickly to each other, interjecting, cracking jokes, and making light of their talents. It’s obvious that their on-screen chemistry is no act. That’s what they’re like in real life.

About three years ago they ran into Tammy McCottry-Brown, host and producer of C2’s The Tammy Show. They said they were performers who wanted to be on her show.

After asking the pair what they would do, she then put PC on the spot, making him sing. “We followed her around like two puppy dogs,” PC says.

“There was a little stupidity involved,” says Sman. “We said, ‘Hey man, I think we can be on TV too.’”

PC and Sman then recorded a mock show to prove their on-camera skills. “It wasn’t like the show is now,” says PC. “It was a variety show with skits. We recorded it in a living room and took that to the station manager, who thought there was something there.”

But the pair didn’t immediately get to work. They spent a couple of years procrastinating. However, the two friends were spurred into action by the tragic passing of PC’s sister and Sman’s mother.

“My sister died two years ago in March,” says PC. “She was 31. She never got a chance to live. I was driving home with tears streaming when I called Sman on the road and said, ‘I got it!’ That’s a reason why we say the barber shop idea was God-given.”

PC and Sman submitted a new seven-minute demo that was much closer to the Shop Talk concept on C2 today. According to the guys, they were told not to get too excited.

“That was definitely a damper,” says Sman. “Just because the demo was entertaining, that didn’t mean it would translate to the screen.”

That said, Comcast aired the pilot.

“The first show was ridiculous, though Sman was good,” PC says, “The second show was a classic. We wanted four shows. Now we’re on our 53rd.”

“Who knew?” adds Sman.

Aside from the addictive banter, Shop Talk‘s popularity comes from its focus on relationships, or as Sman calls them, “boy/girl topics.”

“You have relationships with your coworkers, your loved ones,” PC says. “If they work, then you can be happy. Also, shows that are nichey and clicking always do good. We cover relevant topics. We’re funny and entertaining. And it’s a show where your opinion counts.”

Nichey or not, Shop Talk has become far more popular than PC and Sman could ever have guessed. According to the duo, the demographics for the show are wide-ranging. “It’s not just women, even men come up to me all the time,” says PC. “They don’t hesitate. They consider us one of them. They identify with us and the say thank you for the things we talk about.”

PC adds, “There was a lady in Walmart, in line behind me. She said, ‘I have a question for the Shop Talk guy.’ That was the only reason she lined up! The attendant was also talking to me about her relationships.”

PC and Sman hope to expand Shop Talk with a local radio show, adding radio affiliates before going on to national magazines and networks.

“Whatever happens, we’re gonna be around,” says Sman. “We’re a part of the community. To be able to do something that will help everyone is a blessing.”

Tim Hussey Film Premiere

by Nick Smith February 3, 2010

Lauded local artist Tim Hussey unveils his new documentary Running by Sight on Wed. Feb. 10.

In the 1990s, Hussey’s illustrations appeared in magazines like Rolling Stone and The New York Times. He also worked as art director for GQ, Outside, Musician, and Men’s Health. More recently, he has devoted most of his time to fine art, developing a strong international following for his contemporary work.

Filmmaker Adam Boozer followed him around for a year, recording his life and artistic process. Boozer, an Atlanta native, runs media company Jewell&Ginnie and is the winner of multiple advertising awards. He has recently been recording video for the Charleston Area Convention and Visitors Bureau at explorecharleston.com.

Using Hussey as the focus of his film, Boozer interviews associated artists, gallery owners, and collectors. He also visits the places that inspire Hussey, from the Ladson flea market and the old Navy Yard to rural Southern towns.

After the screening, the film will be sent to galleries to promote the artist’s work and process.

Running by Sight features appearances by Shepard Fairey, Jill Hooper, Rebekah Jacob, and Halsey Director Mark Sloan. The 45-minute film will be shown at the Sottile Theatre, 44 George St.

Personal trainers sought for TV Show

by Nick Smith February 3, 2010

Biggest Loser producers Troy Searer and John Foy are looking for local personal trainers and life coaches for a fat-burning new TV show.

The weight loss series will shoot in Hilton Head, where a trainer will help motivate morbidly obese participants. They are “trying to achieve ambitious weight-loss goals and ultimately change their lives for the better,” states Melanie Halliden, casting producer for Tijuana Entertainment. She says she is looking for male and female trainers, preferably with on-camera experience, who are “no-nonsense while also being compassionate and great communicators.”

The show will air on a major cable network. Budding Jillian Michaels should e-mail Halliden at mhallidencasting@gmail.com with their name, number, e-mail, current location, a recent photo or head shot, a brief bio, and credentials. They should also explain how they would stand out in their approach when helping people in need of their expertise.

COVER STORY Missing the Pointe

by Nick Smith February 1, 2006

Last summer, local media outlets could hardly contain themselves with excitement over the good news: a North Carolina production company called Kearns Entertainment had decided to set up shop at the new Summerville-based ITS Studios for a brand-new hip teen drama in the mold of One Tree Hill, Dawson’s Creek, and The OC. Starring, among others, Tim Woodward Jr., a Georgetown native and Trident Technical College grad, the show, Palmetto Pointe, was not only to be filmed here but set here as well — in the fictional beach town of Palmetto Pointe, S.C. The producers had ordered 17 60-minute prime time Sunday night slots (or 39 including spots for reruns) from the new “i” Independent TV Network (formerly Pax TV), and the show was set to premiere at 8 p.m. on August 28. It seemed that the efforts of so many who had worked so hard to make our state a destination for TV and film production — the S.C. Film Office, the Carolina Film Alliance, state legislators who’d passed big tax incentives to tempt production offices to film here — had finally paid off. The announcement inspired back-slapping and attaboys all around. “It is the end of everything right and the beginning of everything real. That’s what Palmetto Pointe is all about,” Tim Woodward gushed in a hyperbolic press release from the show’s L.A. promotion machine.

And then people saw the first episode, which had a red-carpet premiere at the American Theater on King Street, with all the show’s youthful stars in attendance. And it suddenly seemed that “the end of everything right” was a pitch-perfect description of the show.

Palmetto Pointe went on to complete filming on just five of its 17 promised episodes. From the beginning, the show’s producers hobbled themselves with disastrous missteps — a lack of real funding, untrained actors, terrible sound design, laughable writing, crippling penny-pinching, largely unskilled and non-unionized crew members, and, worst of all, an elephantine sense of hubris about the entire project.

When ITS Studios literally locked the doors and shuttered the windows on the project on November 6 last year — just two months after they’d begun production — it marked the official end of what most observers had long since realized was a disaster of epic proportions. To date, scores of crew members, extras, and other production workers remain unpaid for their work, and the show’s very public failure may well have soured investors and producers on the Lowcountry indefinitely.

If there’s any possible good that might come from the lessons of Palmetto Pointe, it’s that it may serve as an instructive tool in exactly how not to film a prime-time teen drama. What follows are 15 simple steps to creating a television production disaster, courtesy of the makers of Palmetto Pointe.

1. Pick a title that’s both bad and grammatically offensive.

Make sure the name of your show sounds like a low-end condominium development, but add a superfluous “e” at the end to give it the ring of genuine class.

In 2003, Kearns Entertainment owner John C. Kearns’ first TV pilot, Life-N-General, somehow failed to get network bosses begging for more. The self-styled executive producer therefore tried to improve the show’s chances by pulling out all the stops and implementing a name change. The newly titled Life In General followed the growing pains of nine teenagers living in coastal North Carolina, taking a wholesome look at their friendship, faith, and values. The plot centered around ex-high school football star Paul, his chaste friend Casey, and the lascivious Amy. Incredibly, the characters’ love pangs and the show’s new name still didn’t help the show to find a TV slot.

Two years later, Kearns revamped his concept and set his creative sights even lower. Palmetto Pointe followed the growing pains of six teenagers living on the coast of South Carolina, promising to take a wholesome look at date rape, child abuse, teen pregnancy, and baseball. The plot centered around ex-high school baseball star Tristan, who was returning to his hometown with his summer-league team. New, hornier characters were transplanted from North Carolina to a Charleston setting, and Christian themes were abandoned for violent outbursts and angst-ridden whining.

2. Don’t bother to get any real funding in place.

Whatever you do, don’t get funding from a veteran network backer. Instead, find a regional investor with little knowledge of TV budgets or the details of TV production. That way you can cut corners, save a few pennies, and keep your benefactor happy while still reassuring him that you know what you’re doing.

To help finance his prime-time baby, Kearns went to Georgetown real estate developer Tim Casey. But TV production may not have been Casey’s main concern. By the time the first episode of Palmetto Pointe screened last August, co-executive producer Casey’s Harmony Township development was facing foreclosure. According to The Georgetown Times, Casey and his companies were in debt for $429,621 — the kind of press that no self-respecting new TV show wants.

Although the foreclosure notice was dismissed within a month, the Times later reported that “other foreclosure actions have been filed or are pending against Casey and [Harmony co-developer] Brad Jenkins.” Ongoing health problems didn’t help to ease Casey’s cashflow either — according to Kearns, Casey was hospitalized with heart failure in late 2005.

In the first of several e-mails to Palmetto Pointe cast and crew members late last November, Kearns addressed the issue of unresolved payment:

“Subject: Message From John Kearns To Cast & Crew

Dear Cast & Crew:

I thought I would write and update you all on the situation with your paychecks. We understand each of you all are owed money, which the investor has promised on several occasions.

I have been told that the investor is quickly working on freeing up the money to pay for all the debt that the show has occurred [sic].

Please bare [sic] with us as [we] work to resolve this problem as soon as possible.”

That was in November. To date, there are scores of cast and crew members who still haven’t been paid what they’re owed.

3. Let your executive producers cast themselves as leads.

If you’re lucky enough to have actors who’re also producers of your project, make sure they can’t act their way out of a wet paper bag.

Timothy Woodward Jr. achieved an actor’s dream by both executive producing and starring in Palmetto Pointe — his first professional acting gig. As lead character Tristan Sutton, not only could he enjoy some of the creative control that every artist craves, but he could get the best lines and all the glory, too.

Woodward’s Sky Entertainment Group partner was Brent Lovell, another PP production partner. Lovell snapped up the role of Logan Jones, “the all-American heartthrob with a fractured home life.” The two male leads are nicknamed in promotional materials the “Matt Damon and Ben Affleck of the Carolinas.” The origin of the nickname? Casting director David Schifter.

4. Big up your show like it’s the best thing since the dawn of TV

There’s a fine line between advertising your show with hopped-up hype and boasting that the series is better than it can possibly be. Make sure you cross that line.

Hyperbole’s all part of the Hollywood machine, but touting a show as extraordinary before it’s even been shot is asking for trouble, especially when it’s revealed to be nothing but. “Move over One Tree Hill!” said L.A.-based Mayo Communications, retained to promote PP. Comparing it to hit dramas Beverly Hills 90210 and Dawson’s Creek, the media placement experts used a N.C. vs. S.C. angle as part of their initial marketing push. “The big battle is over production dollars,” stated Mayo. “At more than $1 million to produce a show, both North Carolina and South Carolina are trying to keep productions in their territory.”

Mayo was right about one thing; there was a big difference between Palmetto Pointe and One Tree Hill, but it had nothing to do with where they were shot.

5. Buy airtime on a channel with a 50-year-old demographic.

Target your viewers carefully — then put your show on a cable channel that caters to a completely different age group.

Last summer, Pax must have seemed like the perfect place for a teen show. It was changing its name to “i,” the Independent Network, switching from homely shows like Bonanza and Animal Tails to “edgier” stuff (Xtreme Fakeovers).

Pax may have switched its name, but beneath the surface lurked the usual slew of elderly detective shows and Bowflex infomercials. Ads aimed at aging viewers broke up the hot teen action every five minutes or so.

6. Make sure you patronize your target audience.

If commercials for catheters and funeral services aren’t enough of a turn-off, try recycling broad plot devices and character stereotypes from other successful shows.

PP‘s hodgepodge plot featured an abusive dad (played by Dawson’s Creek‘s John Wesley Shipp), a supportive older brother (USA High‘s Josh Holland), a headstrong, mysterious newcomer (One Tree Hill‘s Sarah Edwards), and a kind-hearted bar owner (Nina Repeta, from Dawson’s Creek).

One Tree Hill did have cause to worry after all — PP was treading on its storytelling territory. Troubled teens: check. Problem parents: check. An extremely limited number of spartan sets: double check.

“We were too shackled by our budget to be able to do much of anything as far as production value,” says production designer Geoff Cormier. “It got to the point where I just showed up to improvise with whatever set dressing and props existed at any particular location. Palmetto Pointe was unoriginal and an amalgam of television shows.”

7. Include plenty of jerky camerawork.

Shake it like a Polaroid picture held by a gibbering maniac.

All would-be media moguls know that the teen market is shallow and image-obsessed. So throw in some flashy cars and busty babes in tight dresses if you must, but make sure the camera’s moving too much to show off your assets. Your audience should feel nauseous after each scene.

In the hands of a seasoned professional, shaky camerawork can add realism and tension to a show. In the hands of anyone else, it just looks sloppy and impatient. PP also suffered from the opposite problem — long, lingering, soap opera-style shots that led to awkward, melodramatic pauses.

8. Throw in loads of bad pop music, and make sure it’s so loud it overwhelms any spoken dialogue.

Hey, it’s a teen show and teens like music, right? Give ’em lots of it. The more the better.

John Poppo, a 20-year veteran producer and sound engineer who had worked with *NSYNC, Mariah Carey, Madonna, and Michael Jackson, was hired as PP‘s music producer and supervisor. “I simply got swept up by the excitement, passion, and momentum of the show and its producers,” said Poppo in an early Mayo press release. “I’ve been in the music business for a long time, and I can’t remember the last time I was around this much positive and creative energy.”

So swept up was Mr. Poppo that he provided a veritable sonic boom of ever-present MOR rock nonsense. In a Media Life review, Steve Rosen referred to the “treacly, hyperemotional rock songs constantly bursting out while characters are talking. Often the dialogue is buried by the bad music, leaving one to wonder what’s being said. In the way it uses music, the teen drama comes across as a poor man’s OC.”

9. Ignore sound quality at all costs.

Don’t hire a union-sanctioned crew that knows what it’s doing. Remember that there are a lot of people out there who would give their left nut to work on a prime time TV show. So pick up a few non-union “crewmembers” who will work for next to nothing, and who consequently know as little about genuine production values as you do.

“The producers hired inexperienced people for $200-$300 a week,” says PP lead editor Justin Nathanson, a filmmaker with a decade of professional experience. “For the first episode, they had a sound mixer on set who was incredibly inexperienced — he acted as though he’d never held a boom before. Forty percent of the sound in a scene was unusable. So instead of creating something beautiful, the edit became a turd polish. We had to turn the thing into a music video because the production audio wasn’t up to standard.”

In Episode One, the same images were recycled in a flashback frenzy — a direct result of just such problems. This, combined with the inaudible dialogue, rendered the installment all but unwatchable.

10. Be proud of your bad reviews.

There’s no such thing as bad press — unless it’s really bad.

There were viewers who liked PP‘s first episode, but their voices were drowned out by a swath of negative reviews. Shrewd TV.com critic TV Jesus wrote, “This show is bound to get better. But trust me, no one wants that. Then it will become mindless drivel without any sort of charm or character … I think Palmetto Pointe should be proud of what it is — a poorly polished turd.”

Steve Rosen noted that the debut episode’s poor production values had plenty of room for improvement. “But can the boring, facile, and poorly set-up story be salvaged? Probably not … This is definitely minor-league television.”

The most vociferous comments of all came from a Blogcritics site devoted to the show, occasionally used by pseudonymous cast and crewmembers to vent their spleens. “Denise” described the show as, “about the worst acted and filmed thing I have EVER seen.” Woodward received more than his fare share of brickbats: “The main character Tristan has clearly never acted before,” wrote “George,” “and never should again.” “Chester Rogers” gave PP “two thumbs down, and I wish I had more hands.”

11. Don’t tell your crew anything.

What’s a good youth-oriented soap without gossip? Help it spread by avoiding all communication with your employees, allowing their fevered, creative brains to cook up plenty of ugly rumors.

The purveyors of PP described the show as “one of the most talked-about new teen TV dramas,” and truer words were never spoken — it’s just that all the chatter was shit-talking among the cast and crew. Before the first episode had even aired, a vast rumor mill began to grind, with scuttlebutt flying across the internet and among the cast and crew.

“It’s unbelievable,” says Nathanson, “there are a ridiculous amount of rumors out there.”

Rumors abounded concerning the show’s financial backing, who was getting paid what, and even the star’s hair. The crew’s qualifications were also a major topic of discussion.

“From what I understand,” says Larry Nesmith, a grip on the show, “there were just too many people in positions not qualified to handle them.”

By the time the show had reached its fifth episode, the rumors were flying faster than a plummeting Nielsen rating. Worse, the grapevine chatter could only have an adverse effect on PP’s future and other job opportunities in the area.

“A lot of productions were set to come here and film,” Nathanson believes. “They heard about this show, all the rumors and incorrect information, and that put them off.”

12. When things go completely south, simply shut down production without any warning.

Once your show’s done to a turn, don’t tell anyone you’re going to eighty-six it.

In October 2005, a small group of unpaid, underfed PP extras filed a grievance with their union, AFTRA (the American Federation of Television & Radio Artists). At about the same time, disgruntled crewmembers downed their tools, and union heavies from IATSE (International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees) waded in.

“We were shooting in Ridgeville one day,” says Nesmith, “when we went on strike. We just stood in the local grocery store for half a day. The union came in and got the producers to sign a contract, just to make sure we got better food and paid us what we were due if they were late for lunches.” Nesmith and his colleagues didn’t get a raise. “The union didn’t try to shut ’em down or cost them more money. They didn’t want us losing any more money either, so they came in and did as little as possible.”

With just four hours of episodic TV under his belt, Nesmith was made a full member of IATSE. “I haven’t got my union card yet,” he smiles, “I guess they’re waiting for my dues.”

Nathanson turned up to work soon afterward, in late October, to find the post-production facility at ITS studios in Summerville completely locked. “There was a padlock on the door,” he recalls. “Everybody was just standing around with their mouths dropped open, wondering what was happening.”

Nesmith had a similar experience. “A couple of weeks after the union stepped in, we went to a shoot on Friday night, but no one showed up. Some of the people got paid; a lot didn’t.” Four months later, Nesmith is still waiting patiently for the $1,000 he’s owed, relying on IATSE to keep him informed of developments. Meanwhile, John Kearns has been in sporadic touch via e-mail with his unpaid employees, promising to pay them as soon as financier Tim Casey provides some more dough, which is looking less and less likely.

“People still don’t know what’s going on,” says Nathanson. “With no information from the executive producers, we’re left to think there’s some shady business deal involved. They tore through this town.” One thing’s certain: Casey abruptly stopped funding the show, leaving scenes half-shot and vendors unpaid. Kearns Entertainment was left to foot the bill.

“Kearns had us continue for a couple of weeks with the promise that the money was coming,” says Cormier, “and we were merely in a financial hiccup.” But the cash never appeared, and now former PP production designer Cormier has resorted to small claims court, “to try and recover what I can.”

13. Once the show is clearly and indisputably deader than dirt, insist that it’s merely “on hiatus” and will recommence shooting soon.

Keep the audience’s hopes up — and the creditors away from the door — with the false promise of a sizzling new batch of episodes.

As recently as early January, rumors still abounded that PP would somehow recommence production, with cast members holed up in Myrtle Beach, waiting for their close-ups. “I know people hear that we might be starting back up again once this debt is paid,” Kearns wrote in an e-mail to his crew. “I will say that is Mr. Casey’s wishes.”

“I know that some of the actors have a small salary in a hotel funded by Tim Casey,” says Nathanson. “I hear that they’re going to start up the show again, although that might be a rumor to pacify the people who are owed tens of thousands of dollars.”

With airtime already purchased from i, the producers either have to make more shows or pay back the network’s money. As Nathanson explains: “Tim Casey told me that he bought a season’s worth of slots from Pax. That’s 17 shows, and Casey still owes money for slots that he hasn’t filled.”

“We all know that Casey can’t start production until all debts are paid back,” said Kearns in another placatory e-mail, “and it would be suicide if he did so … I do know that most of the cast have left the area and are back home. They, like many of you and myself, will not work another inch on this show until we are all paid.”

“It would take a lot for me and a lot of others to work on that show again,” says Nathanson. “We all worked 25 hours a day, we all busted our asses helping these young kids and their dreams work. A lot of people moved from out of state, moved their families in and made investments here on the basis of work on the show. As soon as we weren’t worth anything to them, the producers dropped us like a bad habit. We feel kind of swindled.”

“What was most disheartening,” the editor says, “is that by the last episode, 60 percent of the crew had been swapped out and Jason Priestley was executive producing. We were proud of episode five. Then Tim Casey pulled his money out.”

Nevertheless, Nathanson believes that local filmmakers shouldn’t be disheartened by one bad experience. “There are a lot of talented people in town, and Jeff Monks at the S.C. Film Office is doing excellent work encouraging companies to film here. This is fertile ground for the future.”

14. Leave everyone involved with a bad taste in their mouth.

Don’t mess with the laws of nature — TV producers are expected to be inconsiderate and uncommunicative.

“I was surprised at the popularity of Dawson’s Creek when I did the first season,” says Geoff Cormier, referring to the teen super soap, which had a truly terrible pilot. “So I wouldn’t have been surprised if PP became popular, knowing the poor level of TV programming these days. The show was unoriginal and directed by sophomoric amateurs. There were a few ‘stars’ to cameo on the show, but they projected the same desperation for acting jobs as the rest of the cast.”

“[Palmetto Pointe] created a possibility for some other productions to come here,” says Nathanson, but he generally feels that PP had a bad effect on the local industry.

“It was so bad,” Cormier groans, “I’m still convinced it was all a clever scheme for a soon-to-be-released candid camera reality show, and someone is going to show up at my house with a camera crew and yell ‘surprise!’ — we got totally punk’d.

“I’ve always wanted an episodic job in my hometown and an art department to run. I got it, then I got the rug pulled out from under me. I was not surprised, just disappointed.”

15. Point the finger at someone else.

Do your best to be the one riding the white horse.

In a lengthy e-mail to Palmetto Pointe cast and crew members late last November, producer John Kearns addressed some of the issues that had plagued the show in its final days, and which continued to hound it. He finished with an optimistic pep talk.

“I wish to apologize for the delay and major inconvenience this has put you and the rest of the cast and crew of Palmetto Pointe in,” he wrote. “Although it is solely the responsibility of Kearns Entertainment Inc. to make these payments, I completely rely on our investor’s scheduled payments to us for Palmetto Pointe expenses. With him late on payments, we had to shut down and obviously not continue shooting until debt is paid in full and the remainder of funds needed to finish show is placed in an account up front.

“Kearns Entertainment Inc. does not have the money without the help of its investor, so we would ask you to temporarily postpone further legal action to allow us time to get the funds. To be safe I would think at the absolute latest it would be the last week in January for all debt to be paid off. Cast and crew are first on the list and should be paid much sooner if all goes well. I understand if you have to take further action legally, but hopefully we can get you and the rest of the crew and cast paid before then.

“Thank you for your time.”

2010 Charleston Comedy Festival

Found Footage Festival

by Nick Smith January 20, 2010

Before YouTube, On Demand, and DVD, there was VHS. Once upon a time these clunky lumps of black plastic were a godsend to movie and TV junkies who, up until then, had been at the mercy of distributors and broadcasters to get their fix.

So what if the cassettes were unwieldy, noisy, and the tapes got chewed up in your machine sometimes? They revolutionized viewing habits, encouraged a whole new generation of couch potatoes, and enabled thousands of really bad filmmakers to get their projects out into an unsuspecting world.

Like most great inventions, the benign videotape was misused in horrible ways. It could be used to instruct, to market products, to show home movies to your friends. A lot of this was done very badly. But that was part of VHS’ charm — it could provide an alternative to TV, with shoddier, nastier, weirder content that made a refreshing change from network pap.

From an early age, Nick Prueher (The Colbert Report, Late Show with David Letterman) and his friend Joe Pickett (The Onion) scoffed at that pap. Small World, a notoriously execrable sitcom about a robot girl, was the butt of many jokes. “It was horrible,” Prueher recalls with a shudder of delight. “I loved it ’cause it was so bad. I had viewing parties where we made fun of that show.” The sixth graders fostered an ironic appreciation for terrible shows and sought out even worse material, which they found on videos that were so bad people couldn’t even bear to keep them in their homes. In 2004, after years of collecting crappy videos, Pickett and Prueher created the Found Footage Festival. It’s a live show where they screen clips culled from the discarded tapes and rip the piss out of them.

The footage ranges from mullet-packed video dating and Barbie exercise workouts to birthday parties and instructional videos like How to Seduce a Woman through Hypnosis. “It’s like vinyl,” explains the New York-based Prueher. “It was so cheap to produce albums, even a high school marching band could put out a record. There’s some real esoteric stuff out there. Everybody had a home video camera. Even beard trimmers came with a how-to video of how to use it.”

Now that DVD is the format of choice, people are getting rid of collections en masse. That means a thrift store bonanza for the comedy duo, who have been sifting through bargain bins and garage sales for tapes for almost 20 years.

Their quest forms a part of the show’s narrative, before Pickett and Prueher present each clip and put it in context. Their big rule: the footage has to be unintentionally hilarious. If it’s well made, it has no business being in the festival. “We have a montage of VCR board games where you were supposed to interact with your game,” chuckles Prueher. “It was a terrible idea that really didn’t work too well.”

The Footage Festival has worked far better, touring internationally and getting heavy mentions on NPR, Jimmy Kimmel Live, and Attack of the Show. The one-of-a-kind show’s highlights include overacting pirates (is there any other kind?), rapping celebrities, blow gun enthusiasts, talking Rubik’s cubes, and brief, non-erotic full frontal male nudists that will have the audience tittering, not titillated. “If anyone gets any prurient thrill out of this,” Prueher concludes, “there’s something wrong with them.” —Nick Smith

Film Society finds a new space in Park Circle

by Nick Smith January 20, 2010

Ever since he was eight years old, James Sears wanted to run a movie house. When he set up the North Charleston community website in 2008, an online survey revealed that regular movie screenings were a high priority for residents. Here was Sears’ chance. With a small group of like-minded locals, he set up The Greater Park Circle Film Society.

“Our mission is to show great films,” says Sears, “engage the community, promote filmmakers and the art of film while introducing new people to Park Circle.” His personal goals — other than fulfilling a childhood dream — are to “help with film education and contribute to the improvement of the community.”

It hasn’t always been easy to screen classics, independent projects, and documentaries without a cinema. For its first year or so, the Society has used the South of Broadway Theatre on East Montague Avenue, with a portable screen on the stage and cabaret-style seating. Although the theater company has welcomed the “Olde North Charleston Picture House” with open arms, if a play is running on a Saturday night then there can be no screening. Seeking more than a bimonthly schedule, the Society is preparing to move to a new city-owned location in early March.

“We’ll be showing films every Saturday night at 7 p.m.,” confirms Sears, an affable, shrewdly intelligent broker and realtor with his own local business. “That way, if people plan evening activities such as getting something to eat, they’ll always know that at 7, a film will be on.”

The Society’s new location at 4820 Jenkins Avenue was home to the Charleston Area Model Railroad Club until the city ended its lease at the beginning of 2009. The club is now in Citadel Mall, West Ashley. North Charleston Cultural Arts Director Marty Besancon is working with other municipal departments to clear out the club’s O-Gauge leftovers and make sure it’s inhabitable for a wide array of art and civic groups.

“It’s a 2,000-square-foot, open floor-plan building,” Besancon says. “It’s just a big room in a nice location.” Classes, performances, and meetings are being considered for the space, but on Saturday nights the lights will go down and a popcorn machine will crank up.

Smaller buildings like The Meeting Place on East Montague are presently in use. “The City can no longer really accommodate all that folks want to do,” says Sears, “which is exciting.” Ultimately, Besancon would like to see the Jenkins Avenue building revamped, although she says there’s no timeline for this. “I don’t think it would be this year. But lots of folks want to be over there in that wonderful area. We’re definitely running out of space and we want to be able to accommodate growth.”

The Film Society embodies that growth with its increased membership, new equipment, and ties with local organizations. This year the Society will continue its collaboration with the Carolina Film Alliance, Trident Technical College, and Nickelodeon Theatre in Columbia, South Carolina’s only other nonprofit movie house. In March, Lowcountry Local First will be involved in a screening and discussion of The Real Dirt on Farmer John. Later in the year, the Society will partner with The Mill to show monthly cult classic films in the bar’s rear patio area.

When Sears says that weekly screenings at the new venue “will happen,” he has the stubbornness of the eight-year-old who imagined showing movies in the first place. There’s nothing wrong with that. Along with his fellow cinephiles, Sears is a good example of the contribution strong-minded, committed individuals can make to their community.

One boy’s role in a major motion picture helps unlock the door for other children with autism

by Nick Smith January 13, 2010

Braeden Reed is like a regular 7-year-old kid in many respects. He’s got light blonde hair, blue eyes, and a lovable grin. He lives on Daniel Island with his doting parents, attends second grade at the local elementary school. But he’s far more important than he could possibly know.

As an autistic child living a relatively normal life, he’s a testament to the positive effects that intense, long-term therapy can have on the disability. As a smart cookie who needs no extra assistance in the classroom and will probably enter the school’s gifted program, he sets a good example for his fellow students. And as a co-star in the new feature film Dear John, he’s drawing much-needed public attention to autism and the hard-working people who treat it.

In his house, Braeden is doing what any normal kid would be doing, bustling around his spacious living room, playing with his latest toy. On this occasion he’s taking pictures of everything with the Nintendo DS he got for Christmas. Click! He’s got a shot of the fireplace. Click! A snap of the mantelpiece, still seasonally trimmed. Click! There’s a shot of his mom, Adrienne.

She sits patiently watching him. They’ve just been to the park, so she hopes Braeden will have “got his wiggles out.” That’s not the case. He’s full of beans for the next hour, chatting, wriggling, and rolling around as he looks through a scrapbook with mom. Braeden comes across as a little immature, somewhat hyperactive, but otherwise an ordinary kid. But if his mom and dad hadn’t acted quickly five years ago, he might have turned out very different.

Right before he turned two, Braeden was diagnosed with autism at MUSC. Adrienne and her husband Kevin were told that their child would probably be unable speak, or at least hold a conversation. They learned that autism is a developmental disability that affects social and communication skills. Many autistic children find it difficult to talk to or play with others, and they find it hard to comprehend why. They also have trouble dealing with changes in their routine and can become withdrawn or obsessed with specific objects or body movements.

When Braeden played ball, he didn’t understand why he wasn’t as good as other kids. “He wanted to connect, and he was frustrated that he couldn’t,” says Adrienne. “He likes things to be in a certain order. If you tell him you’re going to the ballpark at 4 and it rains, he doesn’t understand that things can change.” Braeden has rituals and patterns that he always adheres to. There are no gray areas in his life-view, only black and white. He excels at things that require logic, but imaginative and abstract concepts are very tough for him; sometimes when his younger brother plays pretend, Braeden urges him to stop. “You’re not a fireman! You’re not an astronaut! You’re Danny!”

Adrienne feels lucky that the autism was spotted early. Under the guidance of local nonprofit organization Carolina Autism, the Reed family did some “early intervention” and figured out what Braeden needed help with. But this wasn’t the kind of disability that could be taken care of with a once-a-week trip to a doctor.

“Braeden’s case is unusual,” says Phil Blevins, executive director of Carolina Autism, “because he and his family have worked very hard to overcome the disabling features of autism. I don’t know what would have happened if his family hadn’t helped him when he was very young. His mom stayed home and worked alongside us on his Applied Behavior Analysis therapy.”

A whole team of people had to become involved in the life of Braeden, his family and his school teachers. According to Blevins, “If everybody isn’t involved, that can really set back the child. Everything we’ve gained in therapy sessions can be undone. It’s difficult for parents to go about their day and do this too.”

Carolina Autism was founded in 2000 by autism experts Blevins and Alan Rose, who is now administrator of the nonprofit agency. It serves people of all ages, reaches hundreds of people every year, and is consulted by groups across the country. “It’s about getting what the child needs,” says Adrienne. “It’s a huge puzzle because everyone’s different.”

The therapists worked on Braeden’s strengths and weaknesses through games and exercises. Cooking and measuring helped him visualize alternate possibilities. Even regular trips to the playground were an essential part of growing his social skills through playing with other kids. The goal was to get him to want to play with them. Braeden preferred being on his own or with his parents. For the most part, the kids he interacted with took his disability in stride.

“We did tons of therapy,” Adrienne says, “but I think a lot of his improvement has to do with Braeden and luck.” The combination of expertise, diligence, and good fortune led to an opportunity that many actors would give their guts for — a prominent role in a Nicholas Sparks movie adaptation.

Sparks’ novel Dear John is about John Tyree, a restless young man who joins the Army in his search for a sense of purpose in life. He falls in love with Savannah Curtis, a wide-eyed college student on spring break. As the War on Terror begins, John feels duty-bound to re-enlist instead of settling down with Savannah. Over the next six years their love is tested to the limit as Savannah falls in love with someone else — and has to write the ultimate “Dear John” letter.

In 2008, director Lasse Hallström (Chocolat, The Cider House Rules) began work on filming the adaptation, financed by Relativity. Channing Tatum (Step Up, GI Joe) was cast as John and Amanda Seyfried (Mamma Mia!, Big Love) as Savannah. Much of the book is set in the Carolinas, and Charleston was chosen as the major location for a combination of aesthetic and tax incentive reasons. For smaller roles and background work, the filmmakers considered local actors.

“It’s a question of economics,” says amiable co-producer Marty Bowen, who is also an executive producer of the Twilight saga. “You can’t just bring in actors from LA. A lot of our extras were students from the College of Charleston.” One young man was picked from a coffee shop because he defined the look Bowen was going for. “What better way to show authenticity than to find a guy with a deconstructionist Beatles haircut, dressed in khaki pants, with his shirt falling out a certain way.”

Bowen and Hallstrom kept up their adherence to authenticity when casting Alan, the autistic six-year-old boy befriended by John. They approached Carolina Autism to teach a child actor how to feign the disability. Blevins immediately gave the Reeds a ring and said, “This is going to sound crazy, but could you bring Braeden to an audition?”

It wasn’t something Adrienne would have done on her own. She’d never entered her sons for pageants or modeling contests. But she thought a movie role would be neat, so she took her eldest to the production office. As soon as he met the director, Braeden crawled onto his lap, took the soft-spoken Hallstrom’s glasses off, and stayed for a couple of hours, proving he could “behave very well.” The spritely sprog understood that it was important for him to obey Hallstrom, whom he aptly described as “the boss of the movie.”

“Braeden had a unique joy and charm,” says Bowen. “We compared that honesty and joie de vivre to kids who were trying to play autistic. The alternative felt forced. Braeden was a good actor, perfect for the role.”

Braeden’s logical cognizance suited the step-by-step filmmaking process. “He breaks everything down,” says Adrienne. “That could have something to do with why he excels at acting.” But although the boy knew what was expected of him, it was still tough to get him out of his everyday routine, not knowing what to expect and waiting around for long periods while shots were set up. He was never predictable, and he rarely delivered a line the same way twice — which made him a risky choice to be in a multimillion dollar movie.

“A lot of times on set, Braeden improvised parts,” recalls Blevins, who was on hand to assist with the boy’s needs and is credited as Autism Consultant. “Lasse would tell him what to do, and he did what he wanted to do.” The nervous Blevins was ready to step in and correct the boy, “but Lasse enjoyed it when he broke from the script and did his own thing.”

Fortunately, Braeden’s unpredictability suited Hallstrom’s organic directing style. “It made the other actors much better,” says Bowen,” because they had to be prepared to improvise off of the text. It’s exciting when that happens.”

There was more to Braeden’s month of shooting than reciting dialogue. The screenplay called for him to be in a scene with a horse, which Livestock Coordinator Dan Hydrick was wary of at first. According to Adrienne, the hard-nosed Hydrick wasn’t comfortable with any child working with a horse, let alone an autistic one.

“Dan was put in charge of seeing if Braeden could go on a horse,” says Blevins. “Dan was against it, he didn’t think it was a good idea.” But over the course of several riding lessons Braeden got used to his horse Honey, and rode her in the movie.

Adrienne watched this progression with pride. “By the time the scene came up,” she says, the rough Hydrick was tearfully advocating for a larger riding scene. “The therapy the horse provided was great to see,” she adds. “Braeden was so tranquil while riding. He and the horse connected so well together. He did better with the horses than the other actors.”

The film had a huge impact on Braeden, both on and off set. Even the simple act of playing with other kids was important. Occasionally, he would stop and think he was doing something wrong, then continue to play. Before he won his role, he would interact with classmates to some degree but he didn’t really understand that he was being spoken to, so he would walk away or ignore them. Now his school friends wouldn’t let him ignore them, asking him what he’d done on set and who he’d met. This led him to communicate with them, encouraged by their continued interest.

Between takes, Braeden would do his schoolwork, hang out with his doubles, and play with Blevins — his favorite memory of filming. By the time his scenes were shot, he’d made an indelible impression on the cast and crew, leaving with his scrapbook packed with photos and comments from Bowen, Hallstrom, and the stars. Click! There’s a shot of Braeden on Honey, with Amanda Seyfried riding alongside him. Click! He’s posing with Henry Thomas (E.T.), who plays his “movie dad.” Click! He’s standing with his two doubles; the first time he saw them he cried, concerned that his mom would “take the wrong Braeden home.”

Shooting continued on the movie through the end of 2008, with the Lowcountry doubling as Africa, Afghanistan, and Eastern Europe for John’s tour of duty. Blevins was on set with Bowen on one occasion when the producer asked him about Carolina Autism and the success of its money-raising efforts. “I told him we were very bad,” says Blevins. “We spend our time working with kids, not going out looking for money as much as we should.”

In June 2009 many families who had been paying for therapy with Medicaid lost that funding. Budget cuts meant that the state couldn’t match Federal Medicaid funding as much as in previous years. As a consequence, families lost out on therapy and Carolina Autism’s budget got smaller. “If a family has some means, we can work out a sliding scale and determine how much they have to do to help us,” Blevins explains. “Some we won’t be able to serve; we have to pay our rent.”

Without funding, many families risk losing their therapy. In July ’08, a bill was passed in the Senate mandating that insurance companies pay for therapy, so some families may be eligible for benefits. But Adrienne has found that “most insurance companies don’t cover treatment. We spend as much as we can on what works the best. These therapists should be making a lot more than they do.”

The producers offered to premiere Dear John in Charleston, with proceeds going to Carolina Autism — as long as the event was carbon neutral. Once Blevins had looked up what carbon neutral meant (it had to be done with zero carbon emissions), he started pestering domestic distributor Screen Gems, making sure the stars could come and getting a date nailed down. Finally, more than a year after the filmmakers left Charleston, they’re returning for a red carpet gala event at the Terrace Hippodrome on the 24th, followed by a lavish after-party at the Aquarium. The LA premiere will happen in early February, the month of the film’s general release.

“Screen Gems is paying for the stars to fly out,” Blevins says, “plus their hotel rooms, stuff to put in the gift bags … all things we planned on paying for.” That will leave more money from the $250 ticket price to go back to Carolina Autism. “We want to provide therapy to everyone,” Blevins adds. “We’re trying to serve more children that don’t have insurance or money. We want to see more kids get what Braeden got.”

Since there are so many different levels of autism, not all families achieve the same success. “Just the chance someone would do this well is why we have to provide these services to as many kids as we can. You never know how well they’ll do.”

The patience and tenacity of Braeden’s parents obviously has a lot to do with his improvement. Mr. and Mrs. Reed can’t believe that at one point he couldn’t talk, and now it’s hard to get him to be quiet — proof that parents will benefit if they, as Adrienne puts it, “stop crying, get off their ass, and do something.” She thinks that Braeden’s role in the movie will be great for autism and early intervention in particular. “So many children won’t be able to speak,” she says, “because parents can’t afford therapy or access to care.”

Braeden has never seen a whole feature film, and he may not sit through all of Dear John. He tried to watch E.T. with his mom, but he only lasted 10 minutes. Nevertheless he’ll be an honored guest at the premiere. “Braeden was a dream actor because of his interesting, sometimes offbeat emotional responses,” says Lasse Hallström. “I was fascinated by his free spirit and his uninhibited performance.” The director says that some of the boy’s choices were “irrational but ringing true. He’s a sweet, smart young man. I look forward to showing his inventive intelligence to an audience!”

The young star attraction says he’d love to do more movies, with two stipulations. First (and most importantly), it has to be fun. Second, he wants to play the role of “Braeden.”

“Whatever he wants to do he’ll be able to do,” says his mom. “The world is wide open for him because of all the hard work that’s been done, and what he’s able to do as a result.” Thanks to Carolina Autism and its fundraising efforts, he won’t be alone.

A look back at the King of Pop’s career on the screen

FILM Michael Jackson

In the austere confines of a German war room, Adolf Hitler attends a briefing with his generals. They have bad news for him.

“Mein Fuhrer. Michael … Michael Jackson has died after going into cardiac arrest. The King of Pop is officially dead.”

Hitler is apoplectic with rage. Turns out he’s Michael’s biggest fan. His tickets for the singer’s new live show are useless. “No one can replace MJ,” he grieves, “not even that little girl Justin Timberlake.”

The scene comes from one of the many parodies of the German film Downfall, in which internet yuksters switch out the subtitles of the film with words — hopefully humorous — of their own. This one’s been doing the rounds since Jackson’s death on June 25 2009, the latest example of his impact on our visually driven pop culture.

Unlike any performer before him, Jackson was always in the spotlight. His TV image may not have been as essential to his career as his music, but it certainly maximized it. By age 11, he was lead vocalist (with brother Jermaine) of The Jackson 5 and making his network debut. His performance on ABC’s The Hollywood Palace included dance moves that host Diana Ross said she “would get arrested for doing.” But when Little Michael twitched his hips or sang about love affairs, it was regarded as harmlessly cute.

Two months after the ABC gig, The Jackson 5 put on a more sanitized routine for The Ed Sullivan Show. It’s no coincidence that the group’s first four singles were all No. 1 smashes. Sure, songs like “I Want You Back” and “ABC” had great hooks, but the Jacksons’ on-screen performances helped to cement their presence in the national imagination.

In 1972, the prodigy had his first brush with movies, singing the soulful theme tune for Ben, a film about a psychic pet rat gone bad. While the rodent was seriously lacking in social skills, the record-buying public hardly cared that Jackson’s single and same-titled album were inspired by a horror movie. In isolation, the ballad was a catchy song about love and friendship. The music mattered more than its less pleasant associations. It wouldn’t be the last time that fans concentrated on the songs of Michael Jackson and not the strange circumstances in which he made music.

By 1976 The Jacksons had switched to CBS Records. Backed by the might of this entertainment behemoth, they got more royalties and creative control, their own prime-time show, and increasingly ambitious music videos. These pop flicks culminated in 1980’s “Can You Feel It,” in which the group towered over a city as giant elemental beings, sprinkling disco-pixie dust on the children of the world.

In 1978 Michael made his movie acting debut in The Wiz, a funky update of The Wizard of Oz. Jackson was the innocent, straw-brained scarecrow, and he proved to be one of the film’s saving graces. The Wiz wilted at the box office, but Jackson was recognized as having genuine acting talent.

The big budget, high spectacle music videos combined with Jackson’s safe, cozy image helped get him on MTV when other black artists like Rick James could not. Just as the ’60s variety shows had boosted The Jackson 5’s sales, videos like “Billie Jean” and “Beat It” helped Jackson’s Thriller album to become the best selling of all time. Most important of all was the 14-minute, John Landis-directed “Thriller” video. When the film premiered in 1984, it was an event, a must-see that brought new viewers to MTV and, with the single, boosted album sales by an estimated 14 million copies over the next six months.

No matter how convoluted or over-the-top the videos were, they had a beginning, a middle, and an end, with a cinematic attention to imagery, sound, visual effects, and choreography. The ultimate expression of this was Francis Ford Coppola’s Captain EO, a $30 million, 17-minute narrative film starring Jackson, which Disney park visitors flocked to see in the ’80s and ’90s.

In many ways, Jackson was a perfect icon for the ’80s, but the opening of his ’88 movie Moonwalker, where leather-clad kids lip-synched “Bad” (opening line: “your butt is mine”), gave the public a clue as to what lay ahead. Five years later the self-coronated King of Pop was facing child sex-abuse allegations. The media that had helped turn him into a superstar was now calling him Wacko Jacko and shedding light on the scandal.

Although no criminal charges were ever brought against him, Jackson paid a $22 million out-of-court settlement, and his career was never as strong again, despite some incredible concert tours and attempts to refresh the public’s memory about his heyday with a HIStory greatest hits collection. He was no longer cute, cozy, or remotely safe.

“Ghosts” was a response to the hassles Jackson was getting from the press and public. In this 38-minute video directed by Stan Winston, a group of townsfolk visit a creepy mansion inhabited by the “weirdo” Michael Jackson. The singer proceeds to indulge in masquerade, high-energy dance numbers, and even a feigned death and resurrection, all in attempts to shock and scare the intruders. The film attempts to revisit the glories of the “Thriller” vid, with dusty dead people shaking their bony booties around a ballroom. But where “Thriller” is held together by a geeky respect for the horror genre, “Ghosts” relies on fake-looking ’90s CGI. Jackson wanted to top “Thriller;” instead he got stuck with Haunted Mansion: The Musical.

Just when everyone seemed ready to forgive and forget Jackson’s purported immorality, a documentary called Living with Michael Jackson was broadcast. An unsuspecting Jackson invited journalist Martin Bashir into his home in an attempt to reconnect with the public; Bashir focused on Jackson’s abusive childhood and his obsession with children, the way he invited them into his bedroom, and sometimes shared a bed with them. Several more accusations of child sex abuse followed (he was acquitted of all charges).

Bashir’s home country of Britain was to host the singer’s big comeback, a run of 50 engagements at London’s O2 Arena. Despite Jackson’s death just before the shows began, enough rehearsals and behind-the-scenes clips were gathered to make a new movie, This Is It. This rockumentary amazed crowds in ways that the performer couldn’t in his later years because of the press backlash he faced. Once again, the music is the focus rather than the three-ring media circus around Michael Jackson.

Now, the Downfall parody’s angry-little Hitler can breathe a sigh of relief. He’ll get a chance to see the King of Pop in concert after all.

FILM The Botany of Desire

The Botany of Desire shows how plants get us to unwittingly do their bidding

Humans aren’t the only creatures on the planet who get horny. Plants can be sex-nuts too. In The Botany of Desire, cannabis growers separate male from female plants. The frustrated ladies produce fulsome mounds of sticky resin, eager to attract pollen. Then the growers harvest the resin for, ahem, medical purposes.

Cannabis is a complex plant that has fascinated us for centuries. This film explores that fascination from the plant’s point of view. Interviewee Michael Pollan hypothesizes that in order to propagate itself, the plant has allied itself with our race. It uses its psychotropic properties to make us go to extraordinary lengths — even risking incarceration — to grow it.

Pollan compares us to bees, which unwittingly help plants spread as they go about their business. Along with cannabis, he looks at tulips, apples, and potatoes. We desire each of these four plants for different reasons: tulips are pretty, apples are sweet, marijuana allows us to momentarily escape reality, and potatoes make good French fries.

Pollan’s investigation is part history lesson, part travelogue, part flight of fancy. He traces apple trees back to central Asia, in the country now known as Kazakhstan. Apples were slowly introduced to Europe and China through trade routes, eventually reaching the New World. The fruit became especially popular here because it could be used to make hard cider. More recently, a few “brands” of apple have been marketed because of their look or taste, leaving their bitter rivals to dwindle.

In another segment, Pollan takes us back to a period of “tulip fever” in 1630s Netherlands, when the price of a single Semper Augustus bulb sold for the equivalent of $15 million in today’s money. The tulip had adapted and mutated to become the most desirable flower in Europe, and if a bulb was scarce enough, speculators could drive its price sky high. When the bubble burst, the economy tanked. This was hardly the plant’s fault, but Dutch tulip bashers still vented their frustrations on any unlucky liliaceae they came across. Again, not a great win for the plant, but tulips have made a comeback since. (Cue glorious crane shots of rows of Dutch flowers, all grown according to color and type then shipped across the world to satisfy our desire for exquisite sights and scents.)

The Botany of Desire is based on Michael Pollan’s 2001 book of the same name. It looks at our world from the plants’ point of view in a clever, entertaining fashion. There are lots of attractively photographed images and the general tone of the film is friendly and informative.

About half an hour is devoted to each subject, with the author appearing as an enthusiastic interview subject instead of presenting his ideas directly to the audience. This gives Botany more of a TV documentary feel. Its caché is raised by Oscar-winner Frances McDormand, who narrates the film and helps the story flow. That flow is only lost when director Michael Schwarz strays from the busy bee analogy and touches on other aspects of the plants.

For example, we’re told that cannabis inspired the discovery and research of the brain’s own “marijuana,” anandamide. This effects appetite, pain, and memory. It’s interesting stuff and fine for a book that has room to meander, but in an overlong film like this one, a tighter focus would only improve it. The digressions detract from Pollan’s point — other species may not have conscious strategies but they can be ingenious, and they have made great achievements. Together we are part of a web of life. Whether it’s by limiting varieties of apples, outlawing cannabis, or trashing tulips, the evolutionary votes we cast effect the world around us in profound ways.

FILM REVIEW The Spiderwick Chronicles

The Spiderwick Chronicles

Starring Freddie Highmore, Mary-Louise Parker, Nick Nolte

Directed by Mark Waters

Rated PG

Holly Black and Tony DiTerlizzi have made a pretty mint out of their series of Spiderwick books, micro-thin hardbacks with high price tags and fine line drawings of goblins and fairies.

Collected together, the books tell the story of Jared, Simon, and Mallory Grace, three children who end up in a creepy house in the middle of nowhere. They find a book written by their Uncle Spiderwick, charting the lives and horrible habits of the fantastical creatures around them.

At first glance, the slim volumes seem unlikely candidates for a Hollywood fantasy movie. After bombastic adaptations of Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, The Chronicles of Narnia and A Series of Unfortunate Events, is there really a market for even more kids’ fantasy?

Or will audiences, as one Spiderwick movie reviewer put it, begin suffering from “fantasy fatigue”?

The answers of course are yes and yes.

It’s happened before, after all, with other genres. Hollywood producers see a trend, snap up the rights to a literary property, and hope the genre element will be enough to pull in the crowds.

Cecil B. DeMille’s success launched many biblical epic imitators; George Lucas’ melting pot repackaging of war movies, westerns, and comic books in Star Wars led to a decade of B-movie space operas. Filmmakers like Roger Corman and Dino De Laurentiis recycled Lucas’ already-recycled ideas and missed the point: The concepts mattered, not the sci-fi trappings.

With Spiderwick the film, the same thing seems to be happening.

It’s a movie of extremes — the first act breaks the cardinal rule of show, don’t tell, giving us far too much information about the feelings and lives of the Grace family through stodgy dialogue. The refreshingly down-to-earth children of the book are replaced by characters who talk like psychology majors.

Simon (Freddie Highmore) explains, “I’m a pacifist. I don’t do conflict.” Uh, thanks for the information on your character, kid. How about giving it to us in a way that doesn’t sound like it’s scripted?

All right, these are New Yorkers so we expect them to vocalize, but these are the kind of children who end a discussion by saying, “end of discussion.” Yet they use brawn, not brains, when fighting the monsters that besiege their house.

The young actors do their best with the material — particularly Highmore in two distinct roles — and there are likeable barely-there cameos by Nick Nolte and Andrew McCarthy. Mary-Louise Parker, who’s normally a strong actress, is the only thesp out of her depth. She misses opportunities to add complexity to her portrayal of a mom who should be on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

When the goblins and sylphs start appearing, Spiderwick goes to the opposite end of the show-don’t-tell spectrum. We are shown almost everything in convincing Technicolor CGI.

There’s a steady pace, a tight running time, and a tear-jerking ending that contrasts the children’s loss of their dad (he’s separated from mom) with their Auntie’s loss of her own father. The audience learns that by looking at things in a different way, you can get a second chance in life, and the children learn that there’s nothing more satisfying than sweet, vicious vengeance.

So what’s to be done to stop the fantasy bubble from bursting the way the sci-fi one did in the ’80s, or the western one did in the ’70s? A refreshingly different approach always helps, and once in a while, an inevitable gem will slip through despite the worst intentions of the Hollywood studios.

Bridge to Terabithia was a surprisingly restrained, child-friendly guide to dealing with loneliness and bereavement. The Golden Compass was a much-hyped primer to the work of Philip Pullman, an author with a healthy skepticism of organized religion. Like the late Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time, The Golden Compass encouraged readers to question blind faith. The latter was bashed by critics like Bill Donohue, president of the Christian League, as “bait for the books.” In his opinion, the dumbed-down, family-friendly flick might lead kids to read the novels and start thinking for themselves.

The best children’s fantasy books balance the teen appeal of adventure fiction and the strange and wonderful ideas that encourage imaginative thought. By watering down the ideas and highlighting the adventure, Hollywood may fill its movie theaters, but without the ideas that made the books intriguing in the first place, the snotty special effects will get fatiguing very quickly.

Fortunately, we’ll always have the books when the next movie bubble bursts.

FILM REVIEW Persepolis

Persepolis

Voices of Chiara Mastroianni, Catherine Deneuve, Danielle Darrieux

Directed by Marjane Satrapi, Vincent Parannaud

Rated PG-13

Persepolis should be a Hollywood marketing drone’s worst nightmare.

It’s the autobiography of uncompromising Iranian writer Marjane Satrapi; it contains too many mature themes for typical pre-teen animation audiences. Its simple art and comic-book origins may put off the older set, too. But it’s an easier sell than you might think: It transcends its medium and tells an engaging story of universal truths in a fast-moving, amiable way.

The story centers on Satrapi’s family life as she grows up in Tehran in the 1970s and ’80s. After the tyrannical Shah is deposed, the people rejoice and gleeful kids play torture games in the street. In this climate of optimism, the fine line between church and state narrows and Islamic dogma steadily restricts the freedoms of its citizens. Tehran becomes a cheerless place that only a Charleston County deputy could love. It’s forbidden to play cards, drink alcohol, hold hands with your boyfriend in public, or generally misbehave.

If Amy Hutto lived in Tehran, she’d be public enemy No. 1.

Some of Satrapi’s neighbors and relatives are imprisoned or executed for their communist sympathies. As if that doesn’t make life hard enough for the outspoken Satrapi and her liberal parents, the city also has the crap bombed out of it during an eight-year war with Iraq. The Iranian government uses the resulting climate of fear to further impinge the civil liberties of its people while they try to continue their lives as normal. As Satrapi’s uninhibited grandma (Danielle Darrieux) puts it, “fear lulls us to sleep. It makes us cowards as well.”

Somehow Satrapi maintains her freedom of spirit, challenging the Islamic Guardians who ensure that women keep their heads covered with chadors and their faces unsullied by makeup. She headbangs to Iron Maiden, attends parties, and continues to speak her mind until it’s not safe any more.

Her parents ship her off to Austria where she discovers sex, drugs, and destitution. Europe has all the freedoms that Iran lacks, but people take it for granted and Satrapi doesn’t find the integrity and solidarity she’s used to back home. “In the West,” she says, “you can die in the street and nobody cares.”

Back home she gets married and learns the value of maintaining her identity and integrity. That serves her well when she moves to France, ready to start a new life as an artist. The animation in this film is Simpsons-simple and stays true to Satrapi’s original comic books (she finds the term “graphic novels” pretentious). The characters have no detailed expressions, just a bump for a nose, a line for a mouth, and pupils like little black beans bouncing around their saucepan eyes.

It’s amazing how much story and emotion is conveyed with such a direct approach. The most effective scenes use silhouettes to show epic events in Iran’s history — riots, battles, executions. We watch the countryside turn from verdant landscape to blasted heath. Satrapi describes walking in Tehran as being “like walking in a cemetery.”

The political asides and mini-history lessons never get in the way of Satrapi’s life story, and the film takes a singularly candid look at a girl’s coming of age — her fantasies, her confusion as she tries to find an identity for herself, and the physical changes she undergoes.

In a clever scene, puberty hits her all at once as she undergoes an awkward transformation from girl to young woman. In moments like this, Satrapi’s self-effacing humor is enhanced by filmmaker Vincent Parannaud’s gift for slapstick and visual comedy, which helps to keep the movie from grinding to a navel-gazing halt.

With Hollywood shying away from a serious examination of the injustices of Islamic fundamentalism, Persepolis is a small, unassuming piece of entertainment with some big statements to make about not just gaining your freedom but what to do with it once it’s won.

FILM REVIEW Rambo

Rambo

Starring Sylvester Stallone, Julie Benz, Paul Schulze

Directed by Sylvester Stallone

Rated R

The world has changed considerably since the last time John Rambo stomped onto movie screens in 1988. His mortal enemy, Soviet Russia, has crumbled. He’s been mercilessly spoofed in movies like Hot Shots Part Deux. Headbands and mullets are the stuff of comedy, not military action. But have audience tastes really changed that much in the intervening years? Have our action hero expectations come full circle?

Rambo — the fourth film in the First Blood franchise — is a loud, exciting, efficiently directed combat movie and the most concise of the series. Not that the Vietnam vet ever stopped to smell the roses, but this is the wrong place to look for narrative twists or witty dialogue. Rambo doesn’t even have a catchphrase or a worthy speech to make. He’s too busy blowing shit up.

The lofty speeches are reserved for a group of missionaries who are trying to bring medical aid and some good old-fashioned Bible schoolin’ to Burmese peasants. They’re led by Dr. Michael Burnett, portrayed by Paul Schulze (Father Phil in The Sopranos). He believes violence is not the solution to settling Burma’s civil unrest. Burnett is accompanied by Sarah Miller (Julie Benz, who played Darla in Buffy). Miller believes “trying to save a life isn’t wasting your life.” Whether it’s because of her platitudes or her naivety, Rambo agrees to take the do-gooders from Thailand to Burma. When the missionaries are attacked, Rambo comes to the rescue with a group of mercenaries. Dozens of unnamed bad guys are killed. And that’s about it.

Judging by the few barely intelligible words that Sylvester Stallone does utter, the lack of a big speech might not be a bad thing. Nevertheless, he’s very effective as the stone-cold Rambo, who isn’t in the mood for a chat. In this movie, he’s a bloody behemoth, crushing every obstacle in his path. His every bootstep makes a resounding crunch on the jungle floor. He causes so much destruction that in New York, he’d be videotaped and codenamed Cloverfield.

Instead, Stallone, who also co-writes and directs, has chosen to plonk his box office monster in Burma, far off the CNN radar, where a true-life war between military forces and Karen rebels has raged for six decades and life is cheaper than a pair of Crocs. Casablanca opened with newsreel-style footage, too, but here the ploy fails; after such graphic images of human suffering, any action flick would seem frivolous. Rambo compensates by upping the visceral violence. The movie’s hardly begun before someone explodes in a burst of gore, and that’s a mere prelude to the carnage to come. It’s a fine screw-you to critics who complain about actioners that show violence without its consequences, but its nastiness prevents the film from working as a piece of entertainment. It’s no date movie, unless your date’s Dick Cheney.

In the ’80s, such realistic depictions of war were just a wicked twinkle in the eyes of Stallone and his writer-director peers, busily trying to top each others’ action set pieces. The First Blood films escalated from the story of a man against an unreasonable rural police chief to a man against a Russian tank division. Standing tall on a heap of possum-playing foreign extras, Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger were more icons than actors, the bastard children of tough guys like John Wayne and Charleston Heston with Charles Bronson as midwife.

We needed those icons. The threat of nuclear war cast a gloom over our existence and the presence of those larger-than-life, muscle-bound Mr. Fix-Its was reassuring. Rambo became such a cozy figure that he got a spin-off cartoon and a toy line. The “support our troops” speeches of his movies may seem overblown now, but back then they were heartfelt. Novelist David Morell made sure there was some rhyme to the violence, but it was facile stuff all the same.

When the Soviet threat faded, we relaxed a little. It was time to lighten up, ask questions first, and shoot later. By then, screenwriter Shane Black had introduced wisecracking characters like Martin Riggs (played by Mel Gibson in Lethal Weapon) and Joe Hallenbeck (Bruce Willis in The Last Boy Scout). These guys were as psychopathic as Rambo, but they had vulnerable spots too. Will Smith and Nicolas Cage later personified friendly guys who just happened to be reluctant heroes.

Now the threat of a Soviet-sponsored armageddon has been replaced by a terrorist-led apocalypse. Our enemies aren’t so easy to identify this time — in fact, they’re more anonymous than all those Russian guards that Rambo used to blow away.

Plus we have a generation of youths experiencing war, and eager for some mindless on-screen action. No wonder Jason Bourne (a character created in the ’80s) has raked in so much cash with his three movies; the character kills with ruthless efficiency and rarely emotes. Bruce Willis has returned for another Die Hard, with less quips this time. Even the devil-may-care James Bond got a gritty revamp, recast as more of a vengeful assassin than a dashing playboy spy.

So Rambo’s back to symbolize our dark times, indestructible as ever. The theme hasn’t changed. Warriors — real and fictional — are necessary, whether we approve of their bone-crunching tactics or not.

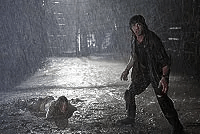

FILM REVIEW The Orphanage

The Orphanage

Starring Belen Rueda, Fernando Cayo, Roger Príncep

Directed by J.A. Bayona

Rated R (with English subtitles)

The Orphanage creeps into American multiplexes with an endorsement from Pan’s Labyrinth director Guillermo del Toro, but it doesn’t really need one. It’s an effective, desperately unsettling ghost story that shows Hollywood how a horror movie should be done.

Above all, The Orphanage proves that it doesn’t take a whole load of CGI or a histrionic music score to create an atmosphere of psychological terror. Less is more.

Simon (Roger Príncep) is a cute 7-year-old boy with an even cuter mom (Laura, played by Belen Rueda). Simon, Laura, and her husband Carlos (Fernando Cayo) move into an old dark house that used to be Laura’s orphanage when she was a girl.

Now it’s creaky, foreboding, and beset by thunderstorms.

As is customary, things go bump in the night.

Simon is adopted, and he gets lonely while he waits for his parents to reopen the orphanage and bring in some new kids with special needs. Like a lot of bored, friendless sprogs, Simon invents some imaginary chums — or are they the ghosts of past orphans?

The movie revolves around Rueda’s performance as she goes from loving mother to tortured soul when her son goes missing at the orphanage’s re-opening party.

Is a mysterious, hatchet-wielding old lady responsible? Is it the specter of Tomas, a deformed little boy who was shut away in the house? Or is Laura going loopy?

Rueda’s excellent. She evokes the weariness of a put-upon parent and a whiff of psychosis without losing the sympathy of the audience.

Cayo is equally believable as Carlos, the family pragmatist. When Laura invites a medium into the house, Carlos refuses to acknowledge the eerie voices of the children they hear. He’s the down-to-earth type whose reasoning fails to track down Simon. Laura’s only choice is to take the medium’s advice and go beyond reason, exploring the ethereal instead.

So far, so derivative — there are shades of Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw, Poltergeist, and del Toro’s own orphanage ghost tale, The Devil’s Backbone. There’s also a nice homage to 1963’s The Haunting when something crawls into bed beside Laura — and it ain’t her husband.