ARTICLES

- Sex

- Voyeurism

- SEWE 2007: Animal Attraction

- SEWE 2007: Animal Magic

- Jack Hanna Interview

- Masterpieces of Dance

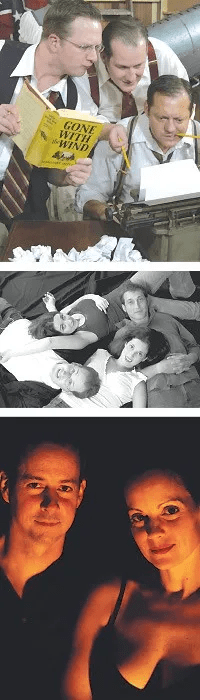

- Amadeus

- The Syringa Tree stage review

- Pecha Kucha

- Monk Business

- The Miracle Worker

- Yankee Tavern

- Charleston gets some Wi-Fi

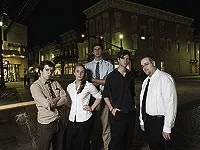

- Elephant Larry

- Beautiful Creatures

- Kenny Z

- Upright Citizens Brigade

- Rob Belushi

- Local Sketch Night

- Fighting Gnomes

- Distracted Globe

- Inherit the Wind stage review

- Steel Magnolias stage review

- Charleston Acting Studio

- Beyond the Gallery

- Florence Foster Jenkins stage review

- Thrive Decade by Decade

- Cage Fighting for Dummies

- Maximum Brain Squad

- Crazy Rednecks

- Gillznfinz

- Spoleto 2010 Preview

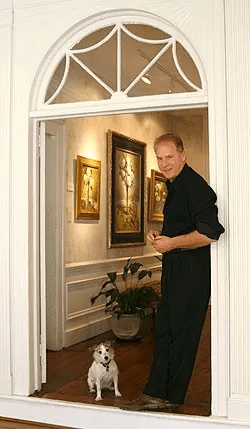

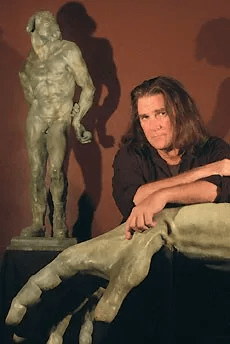

John Carroll Doyle goes Back to Basics

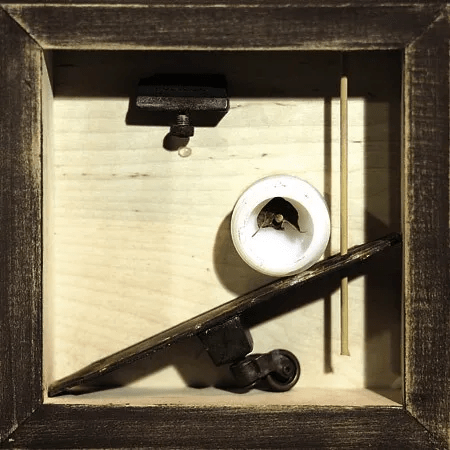

Part of the Furniture art review

The Sound of Music stage review

Double Breasted Mattress Thrasher

A Christmas Carol stage review

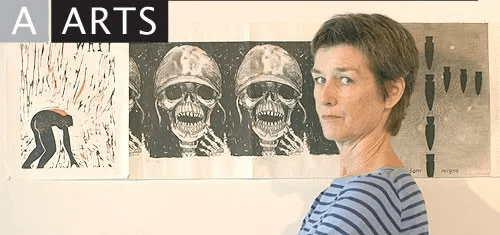

John Hull and Barbara Duval art review

A Little Night Music stage review

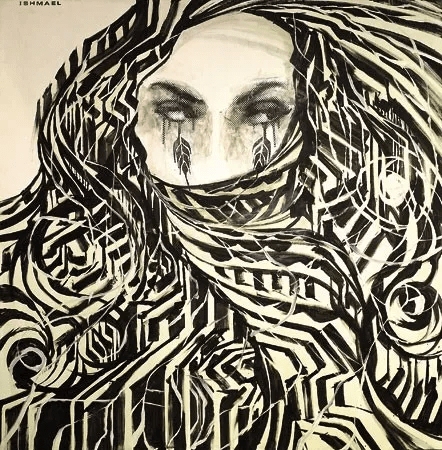

Karin Olah: Incantations in Thread

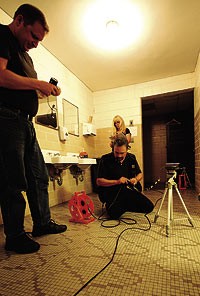

Ghost Hunting with Darkwater Investigtions

That’s So Raven: The Edgar Allan Poe Show

In the Dark: Sean Clancy art exhibit

Glengarry Glen Ross stage review

The Further Adventures of Kevin E. Taylor

Itchy and Scratchy To-Do Lists

Arsenic and Old Lace stage review

Charleston Theatre Overview 2006

The Elams of Second City Chicago

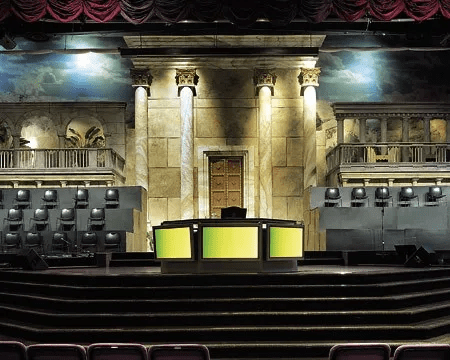

Martin Dockery’s Holy Land Experience

Spoleto Festival USA 2010 Preview

Tim Burton’s The Melancholy Death of Oyster Boy

SEX Private Dancers

by Nick Smith December 28, 2005

“The vice presidency is sort of like the last cookie on the plate. Everybody insists he won’t take it, but somebody always does.”—Bill Vaughan

THE DANCER

Ruth Cole gets paid $25 a night for her work at a local strip club. “On a good night, I can earn hundreds in tips,” she says. “I get to keep what I make on the stage. Private dances are $25, and I keep $20 of that. So when it’s busy, I can make a lot of money real quick, tax free.”

Cole took her job solely to get some serious bucks in the bank. “I’d racked up quite a debt on my credit and store cards,” she says, “and I paid them off in a few months. I bought a car with my earnings and put some into a new house, too.”

Cole has a supportive husband and a couple of kids. She doesn’t plan on dancing for much longer. “I’ll finish up long before my kids are old enough to ask awkward questions about what I do nights. But I feel safe, the customers are polite and I’m doing what a lot of girls can’t — doing the job well, earning good tips, and saving up for the stuff my family needs. What I do is a lot more honest than someone with an office job who uses her looks to get ahead.”

THE BOYFRIEND

Harry Miley dated a stripper for two years. Marie, a College of Charleston student, was looking for a way to make some fast summer cash. “She was horrendous at waiting tables,” says Miley, “so I went with her and two friends to [a local strip club].” Marie was fascinated with the way the women presented themselves, and she got a job dancing there.

“I didn’t have a conflict with it,” Miley shrugs. “I wasn’t all that insecure. I knew that if Marie treated the job as just that — a job — and didn’t mess around with the customers, she’d be okay. I watched her dance a couple of times and it was exciting to see whether she getting more tips than the other girls.”

There was just one problem. Marie needed a few belts of booze before she could get up on stage. “She became very chemically dependent,” Miley recalls. “She broke up with me because she didn’t think she could date me and strip. But we stayed in touch, and she called me one time crying, saying she’d been raped.”

Miley had to draw his own conclusions from the conflicting accounts that he heard. “She’d got really drunk, gone out with some girls from the club and a bunch of men. She passed out in a hotel room and one of the guys took advantage of her.”

After getting fired from the club “for doing something with a customer that she shouldn’t have,” Marie worked nights at another, more seedy establishment. “I was getting calls at 2 a.m.,” says Miley, “and I had to pick her up a lot. She was too drunk to stand up.”

Now school’s out of the question for Marie, but she’s swapped stripping for work with a New York jewelry company. Miley hasn’t visited a club since. “When Marie was moderately sober, she was able to handle any situation. But when she drank she became self-destructive. It’s like modeling or being in a rock band — you’re expected to lead that kind of hedonistic lifestyle.”

THE CUSTOMER

When Columbia native Martin Ward visited a strip club for the first time, he was there strictly to observe. His friend was dating a girl who worked there, and he was offered a free dance. He describes the experience as “an anthropological study,” which obviously required more in-depth research, because he kept going back to the club.

“I felt comfortable in that environment,” says Ward. “It became a hangout at the end of the day, somewhere I could go drink some beer and see some titties in the background.”

After graduating from USC, Ward moved to Charleston. “Out of sheer boredom, I flipped open a phone book and looked for a club. I discovered a more professional establishment than I was used to. I could go there to avoid the college crowds and tourists, and there was interactive entertainment if I wanted it. It became a weekly treat, a Saturday ritual.” Ward got to know the girls there, “as real people, not just entertainers — that gave me an incentive to go back. It broke down the fourth wall.”

Accepted as a regular, he now goes two or three times a week, enjoying the underground atmosphere. “The subcultural side is attractive to me. The people who go there and work there are either rejected by society or rejecting it. A strip club can be so many different things, and it’s up to the customer what it is to them: you can go with a sexual motivation, for entertainment, for company in a Cheers-type bar environment, or just for fun. There’s this great option of making it whatever the hell you want.”

VOYEURISM Confessions of a Junkie

by Nick Smith December 28, 2005

NB: The interviewee asked for his name to be removed from this article after his private life was disrupted as a reult of his confessions. – Nick

“Vice is its own reward.”—Quentin Crisp

“When I wake up in the morning, I put a movie on, then turn it off when I go to work. In the evenings I watch a couple more. I’ll get through about 15 movies a week.

“I started going to movies really, really young. My parents were pretty intense moviegoers themselves and they’d take me to everything. They weren’t shy about taking me to R-rated movies, although I wasn’t allowed to see Silence of the Lambs at age nine or ten. I bought it on video when it came out the next year, watched it in secret, and didn’t tell them.

“I really started going to the movies religiously in the early ’90s, and by 1995 I was in way too deep, watching 20 films per week. Around ’99, when I got out of high school, I got a job working in a video store. I’d rent five and sneak the rest out the back door, bringing them back when I was done.

“Movies are an important source of ideas for me because I’m so closely involved in the local theatre scene — I just graduated with a degree in music from the College of Charleston. Watching videos for the directing and camera angles is fun but it doesn’t have any practical use around here. So I zone in on performances — Anthony Hopkins in Lambs, Robin Williams in Good Morning Vietnam, Orson Welles in Citizen Kane — and I learn from them.

“I also study the differences between then and now. For example, an old musical might allow me to watch Mario Lanza’s technique. You can actually see how he’s making the sound with his body.

“I probably should go outside a little bit more. I used to play sports, basketball, but I’m way too competitive anyway, and I normally watch movies late at night. About three or four weeks ago I was feeling stressed out, fighting with my girlfriend Ellie. There wasn’t the usual hop in my step. It was because I hadn’t been getting my usual fix.

“When I’m watching a movie I’m completely absorbed. I put the weight that’s on my shoulders on the character in the film. Let’s say a rehearsal was crappy and I’ve had a bad day; I can look forward to watching a film where someone’s trying to run a newspaper, or a man’s attacked by a dinosaur. It very much eases the pain of the day.”

FEATURE Animal Attraction

by Nick Smith February 21, 2007

Some say it’s the art. (Though there are those who insist there’s little to no real art anywhere to be seen). Others like the local restaurants, or the historic ambience. But for whatever reason, the Southeastern Wildlife Exposition draws an estimated 40,000 people to Charleston for a single weekend every year. I’d heard enough hype about SEWE to make me wonder what the real fascination was, so I went to find out and discovered a diverse world of chatty painters, Labrador lovers, and seasoned collectors all packed onto the peninsula.

Last Wednesday, purveyors of everything from etchings to duck decoys to African safaris arrived to set up shop. By Friday morning, Marion Square was packed with tents, stalls, animals, and families, the latter drawn to a “Children’s Square” area. In Eudora Farms’ exotic petting zoo, kleptomaniac camels tried to steal the feeding cups from wary young hands and baboons shook their moneymakers. But, pleasingly, the zoo and other attractions like the Edisto Island Serpentarium tent didn’t charge for entry. Sharing an interest in wildlife welfare seemed as important to these organizations as turning a profit; for the many conservation exhibitors in the Square, saving a buck seemed as important as making one.

Tell that to the hunters who like to cull with kindness. Surely it was no coincidence that most of them were placed at the other end of the peninsula, in Brittlebank Park, too distant to take potshots at the zoo creatures. I saw more than one bumper sticker this weekend that read, “Keep Honking, I’m Reloading.”

Not all hunters shoot first and preserve nature later, though. Duck stamp star Jim Killen is a sportsman and conservationist as well as a wildlife artist. A few of his original paintings were on display in the Embassy Suites amid 26 years’ worth of waterfowl prints. These products of the S.C. Migratory Duck Stamp and Print program, which is separate from SEWE but has enjoyed a longtime natural concurrence, were chosen annually to be used as “stamps” for licensed hunters. On Friday, the Suites were quiet and the wide space of the atrium afforded plenty of room to appreciate the paintings from different angles.

Killen is one of several artists at SEWE who’ve stuck around for the long haul — he was Featured Artist back in 1987. Over at the Charleston Place hotel he told me that the one major change he’d seen over the years was an infusion of African-themed art about 15 years ago. “It was at the forefront for a number of years,” he explained. “Now it’s balanced out.”

In Killen’s own work, the balance is tipped in a canine favor. Many of his paintings displayed at Charleston Place were dog portraits. But he’s highly regarded for his waterfowl art as well — in a break from tradition, the duck stamp competition for entries has been discontinued this year; Killen will provide four new scenes through 2010. “It’s one of the strongest state programs in the U.S.,” said Killen, pointing out that print sales support breeding and nesting habitat projects for Atlantic Flyway migratory waterfowl.

Other artists at Charleston Place were just as concerned with wildlife and the environment, and not just in their own back yards. David Kitler sat with a small canvas on his knee, adding the finishing touches to an acrylic piece. “It’s too hot in the jungle for watercolors,” he’s found, “and oils take too long to dry, so I tend to use acrylics.”

Kitler was surrounded by images of the harpy eagle, the world’s most powerful bird of prey, which he’d studied in the Panamanian rainforests. He’s passionate about preserving the eagles and their habitat and aiding the subsistence farmers who live there. “This isn’t just about painting pretty pictures,” he told me. “Through art we can change lives.”

While the animal art at the Expo was rarely life-changing, it was mercifully varied. Kim Shaklee’s skillfully wrought “Nature in Bronze” sculptures rubbed antlers with Larry Seymour’s realistic gouache paintings, Art Lamay’s subtle watercolors, Frank Gee’s bright acrylic boat scenes, Rick Reinert’s plein air landscapes, and Sarah Brown’s blooming flower studies. Like Kitler, many of the artists were happy to discuss their work and their desire to create expressive, exuberant animal portraits.

Nearby, this year’s featured painter Edward Aldrich looked surprisingly chipper, considering he’d been sitting at a table for two days signing copies of his official SEWE poster. Despite a 13-year absence from the event, he felt that little had changed. “There’s classy nature art here, the artists are treated well, and the whole thing’s well-run,” he said. “Other Expos have come and gone. Out west there are more game hunting and safari shows for tour groups, but there’s nothing like this that’s been running for 25 years.”

So maybe that’s the draw — the combination of contented wildlife artists, varied art subjects, and an efficient team of organizers, including President and CEO Jimmy Huggins and Exhibit Coordinator Lainey Halter. SEWE has a reputation for efficiency, and festival organizers deserve it. Sure, everything about it reveals it as the anti-Spoleto — the patrons, the artists, the locations, the politics — but Charleston seems big enough to accommodate both. And, as the local hospitality industry knows, a SEWE dollar goes just as far as a Spoleto dollar.

FEATURE Animal Magic

by Nick Smith February 14, 2007

Once a year a herd of nature lovers descend on Chucktown to graze through an array of wildlife art. The 25th SEWE seems to offer a wider range than ever, with a healthy balance of sculptors and photographers sharing the Expo with 80 painters.

The art will be comprehensively displayed in the Mills House Ballroom and the Grand Ballroom of Charleston Place, with reproductions nesting in the Charleston Riverview Hotel. But after a while, the bewildering scores of photorealist animal portraits, bird scenes, and snow-flecked landscapes are in danger of blurring together in one big zoo mural.

To help make life a little easier for expo enthusiasts, we’ve broken down what’s on offer into a few familiar species, highlighting some superior artists along the way.

Best in Show

Artwise, 2007’s top dog is Edward Aldrich (pictured), nationally known for his lifelike oil paintings. He’s as at home depicting common animals as he is out in the wild, capturing the likenesses of wolves and foxes, lions and elephants, and birds from around the world.

“It’s not realism,” says SEWE President and CEO Jimmy Huggins, “but it’s not so loose that you can’t understand what it is.” Aldrich’s primate portraits are particularly striking, posed on tasteful brown backgrounds. Many of his subjects look remarkably coy, as if they’ve just been caught doing something naughty.

As is traditional, Aldrich will be present in the Charleston Place ballroom to glad-hand collectors and add his John Hancock to a poster of his “Red Fox in Grass,” the official 2007 SEWE image. It’s easy to see why SEWE targeted Aldrich as their featured artist this year. With an all-around interest in animals, he indicates the variety of different subjects in the event and embodies what it’s all about — decorative art with a wild side.

Hot Stuff

“Ten years ago we introduced African art,” recalls Huggins, who’s been with the Expo in various capacities since 1983. “It was really scoring for a while and that waned. Then North American game got more popular.” The cyclical tastes of collectors notwithstanding, there’s still a lot of safari art on show.

Based in Australia, Lee Carter uses pastels to create expressive extreme close-ups of big cats, elephants and monkeys. Her keen eye for detail and fine lines gives the portraits a photographic feel. Peter Blackwell goes for more intense, dramatic, testosterone-pumped pictures of elephants having tusk-to-tusk tussles, and while he’s not averse to painting cute animals in oil or watercolor (such as a zebra family in “A Stripey Hello”), we think he’d rather watch them have a smackdown; two daddy zebras with a grudge go at it in “Clash of the Titans.”

Earth Fare

“Landscapes are popular at the moment,” says Huggins, “because anyone can relate to a landscape; magazines are always showing them and this kind of art puts people in touch with the outdoors without having specific subjects.” The wild vistas also hearken back to American landscape art of the 17th century, a genre that cemented the country’s worldwide reputation as a rugged place of wonder.

Bucky Bowles covers fishin’, huntin’, riverboats, and golf with a light palette that occasionally conjures up an old fashioned, almost sepia effect. Modest rural landscapes like “Early Fall” and “Back of the Hole” focus on picturesque places to fish. D.J. Chapin is less literal in her approach to birds and landscapes, adding a sheen to her oil paintings, “Rhapsody in Gold” and “Nature’s Haystack.”

Plant Life

Not an animal lover? Maybe you’ll go ga-ga over green stuff. Botanical artist Vivian Boswell can re-create a dock leaf in gouache that looks so real you’ll want to pick it up. She imbues her flora with more life and character than some of the doe-eyed animal paintings you’ll see at the Expo. The way she observes and savors life through her work is evident in every stem and vein of her flora.

Elegant Prints

“Original prints” may seem like a misnomer, but when the exquisite art’s by John Audubon and the printing’s courtesy of Robert Havell, the results are worth crowing about. Engravers Havell and William H. Lizars reproduced Audubon’s watercolors for the first edition of The Birds of America back in 1832. While plates from the book often crop up on eBay, these beauties are from the private collection of Gilbert Johnston — no bidding required.

All this means that amidst the brouhaha of naturalist shows and doggie demonstrations, you can track down talented artists who have built up a body of finely detailed work. Don’t look for all your favorites from previous years, though — the roster is rejiggered every year. “Some don’t make it in sales or they’re getting stale,” Huggins explains. “We rotate them, try to keep the show fresh.”

As long as visitors keep flocking back to see the work of so many animal artists all within walking distance, keeping the Expo fresh shouldn’t be much of a problem. »» Nick Smith

Animal Man

by Nick Smith February 13, 2008

Jack Hanna

Gaillard Auditorium

77 Calhoun St.

Jack Hanna has an incredible passion for his life’s work: animal conservation. He loves to talk about animals and interact with them, so it’s no wonder this is the fourth time he’s been invited to SEWE.

The silver-haired Hanna’s no slouch at giving presentations, either. He takes his accessible naturalist talks all over the country, and he’s familiar to millions as a guest on The Late Show and Good Morning America. He’s also the host of Animal Adventures and recently shot a reality show, Into the Wild. He’s director emeritus of Columbus Zoo and Aquarium in Ohio, famed for its state-of-the-art facilities and educational programs. He’s also taken quite a shine to SEWE.

“Nothing compares to it. It’s not just the magnificent artwork; it’s the whole thing,” he says. “A lot of these expos are set up for adults, but SEWE’s fun for the entire family. Whatever income or age group you’re from, there’s something here for you.”

Hanna’s shows will be held in the Gaillard Auditorium on Friday and Saturday. Anyone with SEWE tickets or VIP badges can attend, but if you want to get a ringside seat, we advise you to get there early — Hanna fans usually start lining up an hour before the start time, with doors opening half an hour before the show.

The captivating presentations will include video footage of gorillas from Hanna’s recent adventures in Rwanda. The scheduled menagerie of animals he’ll be bringing onstage includes birds of prey, serval cats from East Africa, a spotted leopard, cheetahs, a penguin, and a flamingo. He’ll also stick around for people who want to ask him questions or get his autograph.

While the exotic animals are undoubtedly the highlight of Hanna’s show, it’s his zeal that really makes this such an entertaining affair. No matter how ferocious or endangered his critters might be, Hanna gives their world a positive angle — looking on the bright side of wildlife.

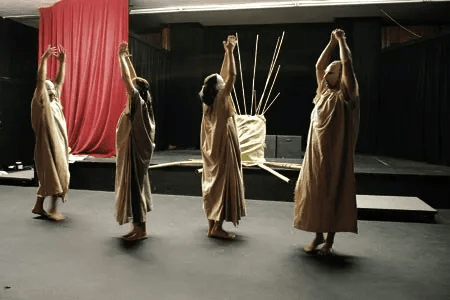

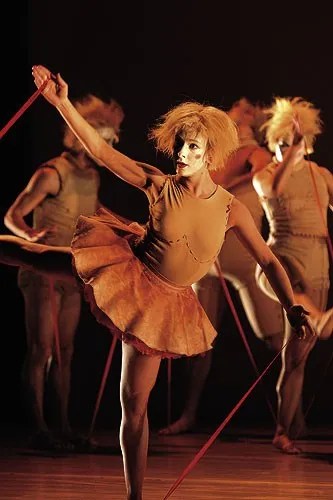

CBT taps some national talent for Masterpieces of Dance

by Nick Smith February 10, 2010

You may not know this, but the Charleston Ballet Theatre is acknowledged as a world-class company. In fact, it’s the only one in the state with the license to perform the works of George Balanchine and Twyla Tharp. Its resident choreographer Jill Eathorne Bahr has her ballets in many regional repertoires, and her version of Dracula is in the repertoire of four national dance companies. Meanwhile, her dancers are well-honed, amazing to watch, and flexible in form and style.

So how do you improve on that? How do you polish a troupe that’s already close to flawless? The answer comes in the charismatic form of Bruce Marks, an extraordinary coach with over 50 years’ experience in dance.

“He’s in constant demand,” says Bahr. “Everyone’s clamoring to get him around dancers. At first, the aura of being around him is so monumental that his instructions go in one ear and out the next. But he says things that you reflect on years later.”

Marks is extravagant in his speech and movement, even at the age of 74. He’s in great shape, and an entertaining guy to watch, hear, and talk to. “If you’re meant for this profession, you can’t stop,” Bahr believes. “He’s the essence of that. He’s a very innovative thinker in the development of dancers — not just understanding the technical aspects, but seeing which dancers can deal with the stress of being on stage.”

Marks is also adept at putting across the idea that dancers have to show the “story” behind their movement — the emotional depth you might find when a character comes to life. “He has the ability of a good storyteller or artist of making people see past what’s there,” says Bahr. “He has a beautiful use of metaphor.”

In a series of master classes, Marks schooled the CBT for their upcoming Masterpieces of Dance — specifically a piece of his own in the show called “The Lark Ascending.” It was inspired by George Meredith’s poem and set to Ralph Vaughan Williams’ music, which used the verse as inspiration. “It isn’t that the piece itself is so remarkable,” says Bahr. “It’s the way he transcended simple postures into the effectiveness of a lark ascending. It really has a Zen, yoga base to its movement.”

Although they’re Balanchine certified, CBT isn’t allowed to slack off. The George Balanchine Trust sends a répétiteur to make sure his pieces are being performed correctly. Jerri Kumery, a Richmond Ballet master, helped to coach the dancers for “Serenade” and “Rubies,” two revered works from Balanchine’s oeuvre that will make up the rest of the Masterpieces. Bahr describes her as “very giving … known for her uncanny ability to offer honest praise or a positive gesture that has special meaning only to that person.”

“Serenade” was Balanchine’s first American ballet, evolving from the classes he taught at the School of American Ballet in New York. The iconic choreographer used the rehearsals to inform the choreography; if a student fell or turned up late, these occurrences became part of the ballet. The Trust calls “Serenade” “a milestone in the history of dance”; it’s traditionally performed by 28 dancers in blue costumes in front of a blue background, moving to the music of Peter Ilyitch Tschaikovsky.

“Rubies” is a mesmeric facet of Jewels, a three-act ballet with no storyline. It’s a brisk, light-hearted piece set to Igor Stravinsky’s Capriccio for Piano and Orchestra.

According to Bahr, the worst fear of a lot of famous dancers is that the next generation will lose touch with the intangible aspects of dance — not the technique, but what she describes as its “mythical side.” By working with veterans like Marks and Kumery, the CBT is helping to keep a century-spanning legacy alive and performing ballet that can’t be found anywhere else in the state.

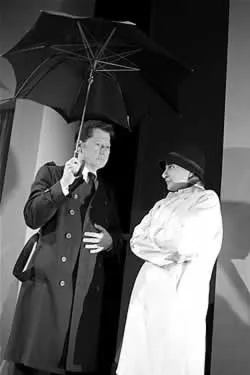

THEATRE Mostly Mozart

by Nick Smith February 1, 2006

Amadeus

Running through Feb. 12 2006

Footlight Players Theatre

20 Queen St.

First, a confession — I’m a fan of Antonio Salieri. Not of his music (although he was talented enough to become Vienna’s Imperial Royal Kappelmeister) but of the man. Like Othello‘s Iago, Salieri embodies all the petty, human jealousies and longings that so many of us harbor. Or at least he does in playwright Peter Shaffer’s 1980 play Amadeus. And as an aficionado of the sympathetic bastard, I wasn’t disappointed by Footlight’s production, which opened last weekend.

As with all great villains, Salieri (played here by Mark Mixson) has his compassionate side. He’s a pious, capricious composer who does good deeds for his fellow musicians and has pledged allegiance to God in return for some musical inspiration and “sufficient fame to enjoy it.” He’s devout enough to keep his hands off his protégé Katherina (Brandi Boone), and he tends to the limited musical needs of ruling monarch Joseph II (Kevin Curler).

Then along comes former child star Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Henry Riggs), who’s way ahead of his time. Not only does he compose complex operas with insufferable ease, but he also acts like a big child. These days, immaturity is tolerated, if not encouraged, in 20-somethings, but back in 1781 it didn’t go down so well.

The battle lines are drawn early on in this play. Salieri and Count Rosenberg (E. Karl Bunch) share Italian chittero-chattero, parrying Mozart’s attempts to curry Joseph’s favor. Baron van Swieten (Scott Cason) and Count von Strack (Bob Sharbaugh) realize that Mozart is proficient, but they don’t care for his childish antics. Salieri alone appreciates the pipsqueak’s music for what it really is — exquisite.

It isn’t fair that the foul-mouthed Austrian should possess such a gift, which Salieri views as a direct hotline to God. So the irate Italian makes his own call to the Lord, vowing to destroy his rival.

Mixson does his best work when he’s speaking to God or describing the passion in Mozart’s music. There’s a heavy load on the actor’s shoulders — he’s the narrator, antagonist, and instigator of events all rolled into one. He does a great job in what at times is almost a solo show, holding the audience’s attention throughout. He trips over a few lines and occasionally he’s too quiet, but perhaps it’s fitting that his words are overwhelmed by Mozart’s notes.

This is a well-cast show, with the actors contrasting with each other through their voices and expressions. For example, as Joseph’s three courtiers, Cason has low, booming tones; Bunch is higher-pitched and wheedling; while the calm, collected Sharbaugh balances the two.

Henry Riggs plays Mozart as a cheeky, immature genius. With a penchant for toilet humor and an occasional, crowd-pleasing cackle, he creates an innocent, well-rounded character. He only struggles with a couple of tough transitions from comic to serious moments that are a pitfall of the play’s rapid pace. Jelena Zerega complements him perfectly as Mrs. Mozart, Frau Constanze Weber, and the capable Cat Cook and Adam McLean provide vox pops as a pair of Venticelli.

The audience enjoys the promiscuous prodigy’s tomfoolery almost as much as Salieri’s machinations. Like a mischievous playwright, the Italian manipulates the characters around him, determined to beat his opponent, God. His careful maneuvering is reflected in the blocking, with a raked stage section and steps positioning characters at different heights depending on their hierarchy or mind state. The play’s visual elements captivate without engulfing the actors, using extravagant costumes and effective lighting to create an operatic ambience.

The set is deceptively simple, with golden trimmings and a very grand piano showing off the opulence of Joseph’s court and Salieri’s house. Wobbly back-projected images help to set each scene. Toward the end, audience members are required to use their imagination, as the squalor of Mozart’s own home is described but not shown — a device perhaps more in keeping with director Rodney Lee Rogers’ minimalist PURE Theatre productions.

Rogers’ assured handling of this play highlights its serious, soul-searching elements, but there’s also plenty of comedy — if you were a guy strutting around in a wig, pink coat, and stockings, you’d need a sense of humor too.

All the world is noting Mozart’s 250th birthday this month. Celebrate it yourself by seeing this prime piece of community theatre, and spare a tear for Antonio Salieri, patron saint of the average Joe.

THEATRE Waiting for the Rain

by Nick Smith January 31, 2007

The Syringa Tree

Atlanta’s Horizon Theatre

Presented by Charleston Stage

Running Jan. 31-Feb. 10, 2007

Dock Street Theatre

35 Church St.

In a theatre not known for economizing on sets or cast numbers, The Syringa Tree makes for a refreshing change. Actress Carolyn Cook tells a simple tale that touches on complex issues of race and identity, building an intimate portrayal of the Grace family, their servants, and neighbors in ’60s South Africa. In the process she gives the production an intimate feel, despite the fact that she’s performing in a 240-seat theatre.

An effective, unchanging set suggests a drought-ridden patch of Johannesburg, with a swing for six-year-old Elizabeth Grace. A lot of Syringa‘s action is seen though Elizabeth’s eyes; Cook captures her innocence, which contrasts deeply with a deceitful adult world dominated by harsh apartheid laws. Elizabeth’s Jewish father Isaac bends those laws, allowing his maid Salamina to keep her child overnight at his home. This contravenes the National Party’s “White by Night” regulation, where black children are not allowed to stay with their parents in white areas after nightfall.

Isaac, Salamina, and her daughter Moliseng are played by Cook with no props or costume changes, as are 23 other characters in an astounding parade of acting prowess. All of the Afrikaner, English, Zulu, and Xhosa characters have distinct, instantly recognizable voices and mannerisms. Many have a particular trademark gesture. Isaac, the wise local doctor, stuffs his hands in his pockets; his wife Eugenie anxiously twiddles with her pearl earring; Mabalel, the skeleton hanging in Isaac’s office, grimaces and dangles its arms. Salamina puts her hands on her hips and dances with the same rhythm and liveliness that runs through the play’s dialogue and all of Cook’s movements.

The events of Syringa are inspired by writer Pamela Gien’s own childhood memories. The play is energized by Elizabeth’s attitude to the events around her — she’s rarely still, jigging around the stage, sometimes addressing the audience and telling them stories, at others looking up at the adult members of her family that Cook then proceeds to portray. It’s never confusing and often a joy to see the actress spin around and become someone new.

As the play progresses, we witness flashpoints in Elizabeth’s young life — the birth and subsequent disappearance of Moliseng, an attack on Granny and Grandpa Grace by a member of the anti-apartheid Liberation Movement, and the poignant fate of her beloved friends and family. Songs, dancing, and dialects add subtle glimpses of South African culture and help to open out the play and give it a sense of narrative unity.

Since Elizabeth’s the main character in the play, it’s lucky for us that director Lisa Adler restrains any potentially annoying little-girl traits. Adler also ensures that the show never gets sentimental, even at a conclusion that’s full of reunions and wistful remembrance. Most of the time, Horizon Theatre’s busy lighting plot helps to suggest shifts in time and location. Only a few swift changes in mood and color seem unnecessarily distracting, as when Cook skips from her doorway to her bed and back again. Along with the lighting scheme, Horizon Theatre provide sound effects that include barking police dogs, aircraft, and insistent drumbeats.

By telling a story of segregation in South Africa, Cook and Adler hope to create fresh entryways into a conversation about racism closer to home. Even if the setting of this play is too far removed for that to happen, it reinforces the importance of family and the incommutability of the human spirit in this rare example of Charleston Stage bringing in another company to do a show. If they’re all going to be as strong as this one, then it’s an experiment that’s worth repeating.

Six minutes and 40 seconds to go

by Nick Smith January 27, 2010

Two weeks ago I got an e-mail from a guy named Terry Fox, a co-founder of Pecha Kucha Charleston (PKC). He asked me if I’d like to be a presenter at their next event. I’d heard of the alien-sounding evening, but I’d never attended. I did know that it involved several presenters who spoke for a short amount of time on a multitude of creative topics. I said yes, and tried to find out more about PKC.

Pecha Kucha means “the sound of conversation” in Japanese. It’s designed as an ideas forum, a creative get-together, a drinking man’s think-tank, an unorthodox networking opportunity, or as Fox described it, “an instrument for engendering dialogue about the arts.” It began seven years ago in Tokyo, spreading like wild rice to 276 cities worldwide.

In 2008, the event was brought to Charleston by a group of locals which included Josh Nissenboim of graphic design company Fuzzco; Beth Meredith of New Carolina, a statewide council on competitiveness; and Patrick Bryant and Robert Prioleau, co-chairs of a creativity committee called Parliament. “We don’t have any titles,” says Fox, “but we do have specific roles, like choosing presenters, finding venues, furniture rentals, and AV rentals.”

Over the past four Kuchas, Fox helped recruit an eclectic bunch of speakers — an urban designer, a book store owner, a conservationist, a fashion designer, actors, chefs, and artists. Their common ground: they’re all creative people.

“There’s such a diverse group of people from all over the community doing all kinds of things,” says Fox. “We provide a forum for their diverse and perverse ideas.”

I visited technical wiz Prioleau, who explained the rules of the night to me. The venue is kept secret until a few days before the event. Each of the eight presenters has six minutes and 40 seconds to say their piece. A countdown clock is projected behind them to make sure they don’t waffle on. A series of pictures, videos, or animated clips stream in parallel with their talk, with the images switching every 20 seconds. Once the clock and the slideshow have started, stopping is not an option.

I didn’t feel nervous about speaking at PKC until Prioleau said, “It can make you nervous, standing up in front of all those people.” Exactly how many people was he expecting? Quite a few as it turned out. The venue was announced: the Terrace Hippodrome on Concord Street, with a 74-foot screen and 400 luxury-size stadium seats. According to Fox, the $5 tickets sold out in two and half days with people looking for spare tix on Craigslist. No pressure.

The popularity of the event owed a lot to the caliber of my fellow presenters. The proceedings were led by artist and motivational speaker Michael Gray, who soon relaxed the crowd with some self-effacing banter. The first presenter was architect Kevan Hoertdoerfer, who showed pictures of natural construction, from bird nests to termite mounds. He compared them unfavorably to our own flawed urban planning. The crux of his talk was that we have to plan for the future, not just the present.

Painter Nathan Durfee discussed his process, observing the world around him to get ideas, drinking lots of coffee to keep himself awake, creating unique portraits out of seemingly abstract shapes and imbuing them with his own personality. Nikki Hardin, founder and editor of Skirt magazine, was just as entertaining. She wasn’t afraid to share her fears, her failures, and her beliefs with us. She made us feel like we were right to break the mold and try something different. These speakers set a high benchmark for the rest of us. Now I was nervous.

As the night progressed, we were introduced to a number of erudite, experienced Charlestonians — photographer Peter Frank Edwards, tattoo guru Jason Eisenberg, webzine editor Caroline Nuttall, and Al Fasola of Current Electric Vehicles. They all had inspiring things to say and found different ways to say them.

About halfway through I stood up to talk about moviemaking, my nervousness gone. Despite the large venue and the cold bright spotlight shining in my face, I could feel the warm atmosphere in the theater. I didn’t recognize a lot of the people there, but I knew we were all brought together by a willingness to be inspired and encouraged by our peers.

Dakpa Topgyal’s journey leads him to spread the Buddha’s teachings

by Nick Smith January 26, 2011

It was freezing cold and pitch dark when Dakpa Topgyal was woken by his family. The 6-year-old Tibetan boy was told to pack his things and taken out into the night. After decades of slow but steady incursion, the Chinese had reached Western Tibet and the Topgyals were no longer welcome. His parents had selected their best yaks and horses for a trek to Nepal. The year was 1968.

Leaving their yak-hair tent behind, they traveled through ice and snow, climbing high over the mountains. It took them several days to reach the Nepalese border, where they had to leave their animals and walk on with only their essential belongings.

Their exodus led to the sweltering heat of Varanasi, an Indian city on the banks of the Ganges. The family was placed in a refugee camp on the city outskirts. The camp was surrounded by a fence that had a high gate and armed guards. Holes were dug in the ground and packed with cartons to make outhouses. Over the course of 45 days, 80 refugees died from the heat. Many of them were cremated in a corner of the camp.

Life got worse for Topgyal and his family. When Southern India accepted 50,000 Tibetans, they were sent directly by train from the camp to Hubli, a major railway nexus in the state of Karnataka. During the journey, Topgyal’s younger brother Sangpo developed a high fever. Unused to the extreme temperature in the train, his parents gave him no water, thinking it would be bad for his illness. Sangpo died of dehydration, and his body was removed by an undertaker, either to be discarded or cremated. The family was never told.

In Hubli, Topgyal was taken by truck through a moonlit jungle. He heard the wolves, wild elephants, pigs, and cobras as he was put in a tent by his parents. Soon after, the refugees moved to a grass hut. This was worse than a tent. The animals made nests in the walls. Topgyal found snakes in his shoes and fighting scorpions would drop onto his head.

Each day, the Topgyals didn’t know where their food would come from or whether they would survive. Sanitation and medical care were practically nonexistent. All the while they thought they’d go back to Tibet. They lived like this for two years.

After months of misery, foreign governments took pity on the refugees and built a camp with much safer brick houses. It became apparent that the displaced Tibetans would not be returning to their homeland any time soon.

On my way to the Charleston Tibetan Center, I wonder what to expect. I’m going there to interview Dakpa Topgyal.

The center is an unassuming white house on Parkwood Avenue, right near Johnson Hagood Stadium. I knock on the door, and there’s no answer for a while. I’m about to knock again when the door is opened by a tall, white-haired man named Leon “Buzz” Edwards, the level-headed treasurer of the Charleston Tibetan Society. He’s dressed in street clothes, friendly and talkative. He ushers me upstairs toward a small office. Documents cover the desk, the chairs are mismatched, and there’s just enough room for three people to squeeze in for a meeting. The place is no different than other nonprofits I’ve visited.

Apparently, Topgyal is in the kitchen making a cup of tea. He greets me and I give the slightest indication of a bow, faintly aware that this is how one shows respect to a geshe, a monk with a doctorate in religion and philosophy. Since it’s chilly in the center that morning, he wears a bright yellow zip-neck sweater over his traditional brown robes. There’s kindness in his eyes, but it appears to be tempered with caution.

In his youth, Topgyal had no reason to become a monk. But as he grew up in India, he saw how devoted his father was to Buddhism. Topgyal’s father was visited every week by his spiritual mentor, who taught him for two and a half hours. The respect paid to this mentor inspired Dakpa. “The teacher was like a most kind parent,” says the geshe. “But I had no idea about the need to preserve Tibetan culture.”

That came later, after the young man trained in the Drepung Loseling Monastery in Atlanta and eventually toured the United States. He first came here in 1993 to increase awareness of Tibet and spread a message of peace and compassion, using lectures, sand mandalas, temple music, and dance as the tools to do it. He visited 97 cities, including Charleston, in more than 30 states across the country.

Tibetan centers are few and far between in the South. There are Thai and Zen Buddhist centers, particularly in cities where immigrant communities have brought a monk with them. But for Topgyal, the Holy City is the perfect place to offer guidance and comfort to people of all religions. “Charleston is more open-minded than most Southern cities,” he says. “Here we provide authentic, traditional Tibetan practices. One day we will see ripe fruit.”

The center is supported financially by devoted members and contributors, with one or two fundraisers held every year. Drop-in visitors don’t have to leave a donation, and they aren’t pressured to return. If students like Edwards are inclined to tell people about the center, they “invite them to come but don’t push them.” He admits that when he tells people of his involvement with the center, “they think it’s queer and strange.” But that doesn’t seem to dampen Edwards’ enthusiasm.

The monk splits his time between here and Columbia at the S.C. Dharma Center, a place for instruction and meditation sessions. In the state capital in 2009, He made a heartfelt speech about China’s grudge match against his homeland. “Tibetans have been jailed, tortured, and killed,” he told his audience. “They have experienced human rights abuses and cultural and religious genocide … because China cannot digest Tibet, despite decades of attempting to do so.”

Remorselessly, China still tries. The Dalai Lama demands autonomy for his country, but not independence. The Chinese consider him a trouble-making separatist. “World leaders should oppose China’s use of Tibet for its own economic, political, and military interests,” Topgyal declared. “[They] should pressure China to change its policy toward Tibet and improve its disgraceful human rights record.”

Rather than condoning the Tibetan riots of 2008, Topgyal asked his listeners to join him in prayers for world peace, Tibet, and the economic crisis. Sitting in his office, I ask him if he feels powerless with his native country under the thumb of a global giant. He shakes his head, relating the situation to two Buddhist terms: ahimsa (do no harm) and satyagraha (insist on the truth).

“One versus many is not overwhelming,” he says. “The truth will never be revealed as false. Lies, exaggerations, and deceptions will reveal themselves as wrong. This was the belief of Buddha, Gandhi, and, I think, Martin Luther King. Once you have trust and insistence in these, the problems will be solved. It might take eons — it is like an elephant facing an ant — but the truth will shine one day.”

For a guy-next-door perspective, I turn to Buzz Edwards, who also believes that “wishing for change, praying, can help.” He uses this positive philosophy in his personal life. He says he’s been volunteering at Roper Hospital since his wife died of cancer. “Sometimes sick people can’t be helped, but you can still give them support.”

Edwards is the kind of open-minded South Carolinian that attracted the geshe here in the first place. A child of World War II, he was fed anti-German thoughts by his father. Growing up as the U.S. went toe to toe with the Soviets, Edwards vividly remembers regular duck-and-cover drills. It was enough to instill disquiet in any child. “They permeate you,” he says. “These delusive emotions not based on fact.” He found that meditation helped. He practiced yoga at Holy Cow and then went to India.

Edwards doesn’t believe Buddhist beliefs conflict with Christianity or Christian services.

Topgyal cites the similarities between Buddhism and Christianity. “The Bible says, ‘As you sow, so you reap,’ ” he points out. “This is karma. What you do today is cause for tomorrow. What you do in this life affects your experience in the next life.”

After more than a decade in Charleston, Topgyal doesn’t consider himself to be a local. But I ask the geshe if life in the States has had an affect on him. “I came here trying to change Americans,” he tells me, “not for America to change me.”

He uses food as an example. “I teach how to prepare homemade, healthy food, and how it comes to the plate. It is a way to gather a family around the table so that they can’t talk and ask each other if they have fulfilled their responsibilities.”

With more than 6 billion humans on the planet, Topgyal doesn’t expect them all to share the same culture. But there’s no reason why they can pay attention each others’ positive traits. Over the past 13 years, he’s developed a distinct perspective on how we live and behave.

“American culture is based on family values, giving, and sharing,” he says. “At the same time, there are some parts of that culture than need to be corrected or avoided, especially overindulgence. When I ask people why there’s so much consumption, they just say, ‘It’s in our culture.’ ”

Topgyal also notes the negative aspects of our independent spirit. “This leads to selfishness and eventual loneliness,” he says. “When children grow, they forget the kindness of the parent.”

The monk also sees too many greedy Americans. “They want more of everything, bigger, better, in a different way. They waste so much food while other parts of the world go hungry.” The geshe sees this as pure negligence. “Why don’t they change these negatives? They expect joy from material things. If they’re unhappy, they go and shop.”

For some, this may sound like a foreigner coming over and criticizing how we live. But Topgyal says it all with a kind expression on his face, charming me with his common-sense attitude. He says what many of us think but neglect to mention out loud.

According to Edwards, visitors at the center include those from a variety of religious backgrounds, including Hinduism, Islam, and Christianity. As he points out, visitors don’t need to be hardcore Buddhists to attend the center. But although a website helps to spread the global word about the Charleston Tibetans, Topgyal doesn’t want folks from his homeland to move here anytime soon.

“Tibetans would sink into American culture like water sinks into sand,” he says. “They would be financially and materially better off. Their lives would be easier, with more physical comfort. But they would lose their family values, and the conflict between their old and new environments would cause psychological illnesses. The young are exposed to Western culture. They think it’s paradise. If they come here, they will have to live and die with their wrong decision.”

Topgyal doesn’t want to transform Charlestonians into card-carrying Buddhists either. For him, a little enlightenment goes a long way. “I’m not a missionary,” he says. “I put no effort into conversion. It’s about producing a good human being. We don’t say, ‘As long as you’re not Buddhist, you’re junk.’ ”

The Charleston Tibetan Society owns a 28-acre patch of land in Dorchester County. This wooded area, roughly halfway between the Holy City and Columbia, is the future site of the Radiant Mind Retreat Center, a place for society members to learn, meditate, and gather. A colorful Tibetan entry gate already stands in place, ready for the rest of the retreat to be built. Designs have been drawn up for a meditation hall, dormitories, a boardwalk, and other eco-sensitive structures.

It’s been a long, rugged path from the Himalayas to St. George, but Topgyal keeps moving forward with determination and enthusiasm. “Love, respect, simplicity, mental wealth, knowledge and wisdom, and strength of heart,” the geshe says. “These are Buddha’s teachings.”

Footlight Players tug at emotions without getting too treacly

by Nick Smith January 26, 2010

Nobody expects the Footlight Players to work miracles. They’re a community theater group with actors and crew of all ages and abilities. Their plays have to be well-known enough to fill a certain number of seats, and most, if not all, of the company members have school or day jobs that distract from preparing for a show.

So it’s a pleasant surprise when a production as capably directed, gripping, and emotionally effective as The Miracle Worker comes along. This stage classic by William Gibson tells the story of a young Helen Keller (played by Eily Mixson), the deaf and blind kid who went on to become an important author and political activist. But to develop from a spoiled shut-in to a college-educated adult, she needs a supernanny.

This game governess is Annie Sullivan (Lara Allred), a 20-year-old Irishwoman haunted by her own long bout of blindness and her dead brother Jimmie (Abby LeRoy). She appreciates Helen’s plight, but she’s also tough enough to bitch slap the blind girl if necessary. And it often is — Helen’s a handful, throwing tantrums when she doesn’t get her own way. It doesn’t help that she’s being indulged by her parents Arthur (David Moon) and Kate (Valarie Kobrovsky). Annie’s challenge is to figure out how to make Helen understand that words relate to the objects they describe — the key to a whole world of comprehension and connection with other people.

The Miracle Worker succeeds because of the commitment of its two leads. Sixth grader Mixson, the director’s daughter, is convincing as the frustrated Helen in her theater debut. Imagine how hard it is to act blind and take a pitcher of water in the face without flinching, and you’ll have a small idea of the girl’s talent. Allred puts across a feisty, quaintly Irish personality with a natural performance that often seems effortless.

Director Mark Mixson is the real miracle worker here, tugging just the right number of heartstrings without getting maudlin. Funny and touching in equal measure, The Miracle Worker provides a full sensory experience.

PURE returns to form with Yankee Tavern

by Nick Smith January 25, 2010

As soon as Yankee Tavern begins, playwright Steven Dietz encourages us to question what we see and what we hear. In a run-down New York drinkery in 2006, Janet is preparing invites for her impending wedding to the owner Adam. We immediately learn that Adam’s guest list is full of made-up or deceased people. They’ve been chosen like characters in a play to conceal Adam’s lack of pals.

Adam’s one real confidante is a lady he doesn’t really want to mention to Janet. He’s been earning extra credit with his International Studies professor. Ray, a tavern regular and diehard conspiracy theorist, spills the beans about Adam and the Prof. This delicate information, along with Ray’s wild ideas about 9/11, JFK, and the moon landing, make Janet doubt her motives and beliefs.

When the low-key Palmer (Mark Poremba, Sea Marks) sidles up to the bar and proposes that some of Ray’s theories are true, Janet’s whole world is in danger of crumbling around her.

All these characters want to believe in something. Adam, portrayed by the handsome and self-assured Will Hodges (Hogs, Dawson’s Creek), has convinced himself that his father did not commit suicide, but was trying to foil a robbery instead. Janet indulges Ray and sees kernels of truth in his circumstantial scuttlebutt. Palmer believes he can make a difference by warning Adam that he’s in danger. Ray has “an enormous capacity for belief.” He thinks that the truth will come out if enough people question the lies around them.

But Janet is the focus of Yankee Tavern. Katie Huard (Mauritius) gives the character enough depth and range of feelings to maintain our sympathy throughout. She is serious without being gloomy, and when she gets upset, it’s consistent with her emotional development. We believe her.

Hodges can be likeable and assertive when the plot requires, but there doesn’t seem to be enough of a build-up from Ray’s assertion that Adam’s dad killed himself to a subsequent argument between the two men. During the first act, the writing seems to suggest that he becomes increasingly frustrated with Ray. That isn’t consistently shown. The brief lovey-dovey moments between Adam and Janet don’t ring true; the kisses are too chaste, the embraces almost non-existent. This is supposed to be an engaged couple, not a married one.

In a smaller role, Mark Poremba (Sea Marks) plays Palmer with great presence and assurance. Not everyone can make sitting at a bar look interesting, but he does it. The real star of the show is Equity actor Randy Neale (The Seafarer, Killing Chickens), who gives the potentially crackpot Ray plenty of complexity.

Neale certainly has lots of good material to work with. He makes the most of his funnier lines (“I’m not a vagrant, I’m an itinerant homesteader”) without breaking character. He gives us food for thought; for example, he points out that the planet doesn’t need to be saved, we do. The planet will do just fine whether humans are here or not, it’s just a ball of rock. He even makes an overwritten line about “rats like a shimmering gray carpet” work.

Aside from getting convincing performances from the actors, director Sharon Graci also makes the uneven play work as a satisfying story. She makes some strange choices in placing her actors — they sometimes perform with their backs to the audience, and Poremba is seated upstage at the end of the bar so other actors have to turn away from us to face him. But this certainly helps to suggest messy tavern life in the most intricate set PURE has attempted in years. Michael Moran (set construction/design) and Chris Romano (props/set) actually make the proscenium look larger than usual with a mirror, liquor bottles, a jukebox, sturdy chairs and tables, and louver doors.

We may not accept everything that Ray tells us, but you can believe this is a return to form for PURE Theatre after the lighter, less polished It’s A Wonderful Life. Conspiracy theorists and fans of the company will not be disappointed.

FEATURE No Strings Attached

by Nick Smith January 25, 2006

For a while now, the City of Charleston has been exploring ways to provide wireless internet access to users on the peninsula. The launch has been pushed back a couple of times — a soft opening of the service was initially planned for November 2005, then mid-January of this year. But it’s finally about to become a reality, without taxpayers getting shafted in the process.

The job’s been farmed out to two companies — the Charleston-based Evening Post Publishing Co., which owns The Post and Courier, and Widespread Access, a telecom company with a Mt. Pleasant HQ. Together they’ve formed AccessCharleston.com and in exchange for agreeing to invest approximately a half million bucks in the service, the suppliers have won a five-year contract.

Evening Post Publishing plans to make back its investment by selling more newspaper subscriptions to users and online ad space to businesses. Widespread Access, meanwhile, will offer bumped-up subscription packages with faster access and more bells and whistles.

“We’re throttling free access at 250KB per second,” says Sam Staley, president of Widespread Access. Even so, at around 10 times the speed of a dial-up connection, that should suit a casual user. “We’ll probably charge $19.99 a month for a higher speed,” he says. The company plans to offer one megabyte per second to start, with up to three MPS soon after — enough to check out the other incentives available. “ESPN 360 is one that we’d like to include,” says Staley, “that’s been a popular request.”

Using a mixed bag of nodes, phased-array panels, and mesh networks (if you have to ask, then you probably wouldn’t understand the answer), WA’s aim is to offer 90 percent outdoor and 70 percent indoor coverage across the lower peninsula for its rollout. “Our goal is for it to be a ubiquitous service,” says Staley, “with a grand opening on March 31. But at least some of the service should be available by the end of January or February 1.”

Indoor users unlucky enough to be in the remaining 30 percent or live just outside the six-mile coverage area will be able to purchase wireless modems to boost their reception, and it’s not just public spaces or participating businesses that will get the signal. That has been the case in the past, with Chamber of Commerce-sponsored areas dubbed “Thinkspots” established in 2003 that can be used with prepaid cards.

“The U.S. has gone from number one to number 16 in the world for broadband usage,” says Ernest Andrade of the Charleston Digital Corridor, a knowledge based company with partners in the private and public sectors. “We want to slip away the impediments to broadband usage.”

For Andrade, Charleston’s WiFi venture is a testament to dogged execution. “We just stay in the trenches,” he says. “For me, the drivers are legislative, political, and content-oriented, not technological. The most significant aspect of the WiFi project is that it doesn’t use public funds.”

The involvement of a media company will help to take the edge off arguments from existing service providers that the competition’s unfair. Big-name broadband providers like BellSouth and Comcast started bellyaching when Columbia decided to plan a WiFi service last year, and the bitching has only increased in volume with Charleston’s plans. But the big telecom companies will still have far fancier content than WA’s effort. “Our biggest rival is content,” says Andrade. “As hardware becomes more robust and mainstream and less expensive, there’ll be an increased usage of broadband across the board.”

Although it’s footing a sizeable portion of the bill, Evening Post Publishing will save a few pennies by recycling content from its P&C website, Charleston.net, for the new WiFi site. “When you connect you’ll be greeted by a portal to the City,” Staley explains, “with location and time-based information. It’ll act as your entryway into what’s going on in Charleston.”

There’s still a long way to go before everybody has WiFi access. The providers hope to extend their service beyond the peninsula in the near future, working in phases and involving users in their plans. “This is an open network,” Staley states, “we want people contributing to it. It’s a community-type portal.”

The way Andrade tells it, the success or failure of the service rests on the users. “It’s the community’s role to validate what’s going on,” he says. “This is just the beginning. But it can definitely be used as a model to stimulate economic growth.” Even if the new service doesn’t encourage that growth, it’s worth establishing just to see the phone and cable companies sweat.

Elephant Larry

by Nick Smith January 20, 2010

We’ll never forget Elephant Larry, the five-strong comedy team from NYC. These doyens of dumb humor brought their sketches here twice in 2006, for the Comedy Fest and Piccolo. This time they’re trumpeting a Greatest Skits package, with a random assortment of jokes, songs, and pop culture spoofs.

“We have a closing number called ‘The Clothes Song,’” says co-founder Geoff Haggerty. “I teach the rest of the group how to wear clothes, but I don’t know how to do it either. It’s fun to do, all the characters are stupid, but we have to rehearse to get it stupid in the right rhythm.”

The group has won multiple awards in its seven years of existence, from the Audience and Jury Awards at the 2004 Bass Red Triangle Comedy Tour to The Village Voice’s Best Comedy Ensemble of 2009. Their painstakingly unintelligent humor draws inspiration from their idols Monty Python, Kids in the Hall, and Second City, although they have a silly style all their own. “We sometimes do wordier sketches and ones that are thought out,” Haggerty says, “but more than anything we want to convey how much fun we have doing them. We’re energetic on stage.”

That energy has translated well to the internet, where the group has had considerable success with short comedy videos. They’re probably best known for “Minesweeper: The Movie,” an elaborate adaptation of the desktop game. “That got over a million hits on YouTube and three million on another site,” says Haggerty. John Landis (Trading Places, The Stupids) directed their JibJab.com competition entry, “Tall Cop, Short Cop.”

“I watch those videos, and I’m surprised by how far we’ve come,” Haggerty continues. “Even ‘Minesweeper’ was two and a half years ago. The stuff we’re not so proud of, people don’t watch anyway.”

Instead of waiting for someone to hand them a silver-plated deal, the comedians make their own TV pilots and web series. “We funded, filmed, edited, and wrote a pilot last year,” says Haggerty, then checks himself and cracks a joke. “Writing it was the last thing we did, because we thought we should have a script to put the random stuff we shot into some kind of order.” It comes as no surprise that if the group ever has a chance to fool around with a concept, they run with it as far as they can without leaving their “comfort zone” of effective humor.

Haggerty is itching to perform one of his favorite songs, “Sitting on a Bear” (a parody of Bon Jovi’s “Living on a Prayer”). One of the team, Alexander Zalben, has just become a father, nixing their plan to parody the Jerry Bruckheimer/Nicolas Cage movie Con Air on stage (Con Bear, maybe?). But Haggerty, Chris Principe, Jeff Solomon, and Stefan Lawrence will all be present with a “whole new package of stuff” for Charleston audiences.

Locally-based YA novel mixes Southern with supernatural

by Nick Smith January 20, 2010

Never underestimate the lure of the Lowcountry. As teen fiction authors Kami Garcia and Margaret Stohl have discovered, there’s an international fascination with our landscape and Southern Gothic heritage.

Garcia and Stohl’s first novel is the surprise hit of the season. Beautiful Creatures is number three in the New York Times bestselling chapter book list and got to number five on the Amazon’s Editors’ List of the 100 books of 2009. It’s set in Gatlin, a fictional town near Summerville and Lake Moultrie. Gatlin harbors dark supernatural secrets, as high schooler Ethan Wate discovers when he falls in love with the mysterious outsider Lena Duchannes.

Lena lives in Ravenwood Manor, an old house neighboring a plantation. Like the town, Ravenwood has its secrets. With twists and character developments in every chapter, the authors have gripped teen readers in 26 different countries.

“It’s amazing how far a supernatural and teen reach can go,” says Stohl. “We met with our French fans, chatted on our Spanish fan site, and talked to our German publisher. The Germans are really interested in food.”

Although the writers live in LA, Garcia has strong ties to the Southeast. “Charleston is my favorite southern city, I’ve been there a million times,” she says. “My family is from North Carolina.” While researching the book, the authors visited Lowcountry plantations, looking for houses and land that backed up to the Ashley River. They were particularly inspired by Magnolia Plantation with its moss-covered oaks and cypress trees. “We’re captivated by the strong sense of place here,” says Garcia, who returns to Charleston with Stohl this week as part of an extensive book tour.

Listening to Garcia and Stohl, you’d think they’d been writing books together their whole lives. But, while they’d been reading each other’s writing for a long time, their first full-length collaboration was spawned over lunch a couple of years ago.

At first, Beautiful Creatures wasn’t a novel at all — it was a series of installments written for an eager audience of seven teenage girls. “We just wrote it for our daughters and their friends, and put it online for their friends,” says Garcia.

“They shaped what happened in the book,” adds Stohl, “through the questions they asked about characters and what would happen.” That way the writers knew what their target readership was interested in — and they had to keep going. “The girls dared us to write it, and they were our taskmasters. We’d come home and they’d ask, ‘where are the new pages? You didn’t do anything, did you?’”

The completed story was read by Stohl’s oldest friend Pseudonymous Bosch, who writes the “Secret Series” of books for grades 4-6. He gave it to his agent.

“I got a call from someone,” Stohl says, a tone of I-can’t-believe-it wonder still in her voice. “I didn’t know who it was. I was just excited to get a call from New York. But when I got off the phone I told Kami, ‘I think we have an agent.’”

The wonders continued. The hotly sought-after manuscript found a place at Little Brown; before the novel was even published, it had a Warner Brothers movie deal. So what is it about this supernatural romance that has publishers, editors, and filmmakers so spellbound? Stohl has a theory. “The teens we wrote with felt that there were themes they related to — feeling powerless, wanting to make decisions for themselves, feeling controlled. The idea of being truly powerful and going against the grain resonated with all seven people.”

“They want to be individual and express who they are,” says Garcia, “but also have friends and fit in.” With its milieu of sorcery and Civil War history, Beautiful Creatures explores all these subjects via a coming-of-age story that authentically channels the authors’ inner teen, and the dark side of Charleston that fascinates people so much.

2010 Charleston Comedy Festival

Stand Up Showdown with Tig Notaro and Kenny Zimlinghaus

by Nick Smith January 20, 2010

Stand up comedians Tig Notaro and Kenny Zimlinghaus(aka Kenny Z) have very different expectations of Charleston. Notaro, best known for her role as tough gay cop Officer Tig on The Sarah Silverman Program, imagines “being picked up from the airport and taken from show to show in a horse and carriage.” Otherwise she’ll be disappointed. Festival veteran Kenny Z just expects locals to be “blonder” than his regular New York audiences.

“I’m always careful when I come to Charleston,” he says, “because I’ve caught myself too many times staring too long at what I thought was a hot blonde long-haired girl only to find out it was a surfer guy… still hot though.”

Tig Notaro

Tig Notaro is a non-blonde Comedy Central darling with a solo half-hour special and guest appearances on Dog Bites Man and Premium Blend. She’s also performed on Last Comic Standing, Jimmy Kimmel Live, Last Call with Carson Daily, Comics Unleashed, and Showtime’s Live Nude Comedy! The Jackson, Mississippi native’s routines are part languorous subtlety, part acid wit. Time Out Chicago once described her as “a Steven Wright and Bebe Neuwirth love child.”

With deadpan delivery, Notaro’s routines often include comments on her childhood, school years, and real-life encounters with strange people in public places. Her best known bits include “little titties,” inspired by a crude comment made by a passerby, and “No Moleste,” riffing on the leering lobos at a Mexican restaurant.

Notaro says that comedian Todd Barry encouraged her to come to Charleston. “I don’t typically trust Todd, so I’m not sure why I listened to him this time.” But she’s looking forward to finding out what our comedians are like. “I think the only comedian I know from those parts would be Aziz Ansari,” she says. “I can’t imagine he represents the scene. However, I’d be very pleased to find that the area is riddled with young male comedians from India. What a fun surprise.”

Kenny Zimlinghaus

In the second half of the Stand Up Showdown, Kenny Z will be trying to get in touch with his feminine side. He’s currently co-hosting SIRIUS-XM’s Cosmo Radio every morning on Channel 111 and XM162. “I talk for four hours every day and I get weirder and weirder,” he says. “I state what I think is true. The things I say don’t fit in, and people laugh at it.”

On his radio show, Z covers “all the things I’ve learned about girls over the past three years,” which he’s looking forward to sharing with Charleston audiences.

Z is a stalwart of the festival. Longtime comedy lovers will remember his Comedy Free with Kenny Z show in what used to be Bar 145 and 96 Wave’s late, lamented Storm & Kenny Radio Show with Stupid Mike.

“Every time I come I try to do everything different,” says the comedian. “I’m always working on stuff, and I use Charleston as a testing ground.” He describes his style as observational funny stuff. “It’s not too offensive, I don’t care to be. Mainly it’s just me, stranger than ever.”

The Upright Citizens Brigade Touring Co. presents Pangea 3000 and Sidecar

by Nick Smith January 20, 2010

If an asteroid was heading straight for earth, and we were faced with the annihilation of society as we knew it, the best comedy sketch groups to get caught in a comedy venue with would be Sidecar and Pangea 3000. At least you’d die laughing.

Both New York groups have previously built half hour shows around the apocalypse, and they both manage to make the end of the world funny as hell. Their show is being presented by the Upright Citizens Brigade Touring Company.

Pangea 3000

Pangea 3000 will open the show with a selection of their favorite skits. Dan Klein, Arthur Meyer, Zack Poitras, and Seth Reiss are all contributors to The Onion and perform at the Upright Citizens Brigade Theater. Klein describes their humor as “playful, with the sense of silliness of a five-year-old combined with 100 combined years of comedy knowledge and expertise.” Hence their laser-tagging raptor logo — it looks silly, but it’s also a potent blend of ancient and high-tech.

Pangea strive to be new and unique. “We’re always asking ourselves, ‘Is this funny? What is comedy?’” says Klein. Combining this self-analysis with daft noises and fart jokes, the foursome start weird and get funnier as they go. Past examples of their absurdist sketches include acting out an incomprehensible Japanese videogame, pranking each other with a whoopee cushion, and a scatologically inspired spelling bee.

“We’re always finding new ways of being funny,” Klein says. “We’re so jaded, we work in comedy and we all watch so much. If something isn’t genuinely making us laugh we don’t have the heart to put it on stage.” The guys spend a long time on their scripts, constantly rewriting as they gauge audience response.

“When we first started we were slaves to the scripts,” Klein remembers. “Now we follow them pretty tightly but let ourselves go in the way we approach them.” So the way a sketch is performed can change if the mood takes them. We anticipate a funny, farty, and slightly surreal half hour that will leave audiences dazed but desperate for more.

Sidecar

The young men from Sidecar take well-known situations — an awkward date, cops interrogating a suspect, a man’s voracious hunger for pizza — and twist them in bizarre ways. The date ends with a Mario Bros. battle. The cops keep losing their handcuffs. And the pizza teases the man with its doughy tastiness throughout his life. Co-writer/performer Matt Fisher describes their compilation show “This One’s for the Losers” as “strange.”

Sidecar tour extensively. “It allows us to put our material in front of a wider variety of people,” says Fisher, who is joined by Justin Tyler and Alden Ford. “But our core audience is probably pop-culturally literate, over-stimulated young people.”

One of their signature shticks is an homage to early 20th century comedians and singers. “There will be waxed moustaches,” Fisher smirks. One of their funniest past sketches starts with a stand up comic called Nick Deebs, who has filched his material from a 1920s performer who jumps on stage and does the routine in perfect period fashion, complete with Edwardian hat and, yes, a mustache.

Whatever form their cutthroat razor-sharp comedy takes, Sidecar’s skits are guaranteed to be unusual and unpredictable.

2010 Charleston Comedy Festival

BS (Belushi and Stoltenberg) & Eliza Skinner is: SHAMELESS!

by Nick Smith January 20, 2010

Some comedians give the audiences exactly what they want — straight laughs, no chaser. Others are more masochistic, pushing themselves to invent new characters and situations that are harder to sell to the crowd. But once they do, the payoff is far more satisfying.

The double bill of Eliza Skinner and B.S. is full of twists, turns, and outrageous individuals. The first half is a scripted trip to the world of New York narcissism. The second pairs Dad’s Garage alumnus Tim Stoltenberg with Rob Belushi, who continues the Belushi family legacy of unforgettable comedy.

Eliza Skinner is … Shameless!

Eliza Skinner (I Eat Pandas, Baby Wants Candy) knows something about being shameless. After all, you need to have some brazen qualities to write and stage your own 30-minute one-person show. But the Queens-based Skinner has examined that compulsion to take center stage and uses it to inform her portrayals of three hateful, blatantly self-centered women: arrogant Karen, youth-obsessed Debra, and Amy, the man-chasing party girl.

“I wanted to create characters who were all pretty unlikable, then try to make them likable for the audience,” she says. “I was trying to see how much I could get them to care about the characters.” Quite a lot, apparently — she earned a glowing review from Time Out NY, which promised “you will love her.”

Each twisted woman is visited three times. They’re desperate for adoration and shameless about how they get it. Although the characters are products of Skinner’s imagination, she has taken some juicy details from real life. “There are all kinds of people [in New York], driven about what they want to get. That leads to some shamelessness.”

The show finds humor in the “horror of people in life who you can’t stand, but once you get to know them they’re not so bad.” Skinner doesn’t have to yearn for attention — she’s beautiful, wickedly funny, and spot-on with her investigation of the human hunger for the spotlight.

BS: Belushi and Stoltenberg

While Karen, Debra, and Amy spout more than their fair share of egocentric bullshit, Shameless! is followed by a different, improvised kind of BS: Belushi and Stoltenberg, a two-man team from Chicago that makes light of topical news, politics, history, and personal observations.

Rob Belushi’s incredible resume includes work with Second City, The Steppenwolf Theater, New Line Cinema, and his dad, Jim (John Belushi was his uncle). Three months ago he performed a one-off show with fellow Second Citizen Tim Stoltenberg. “We felt good about it, didn’t want it to end, and stayed in contact afterward,” Stoltenberg says. They could smell success and that smell was B.S.

The comedians’ fast and furious 30-40 minute set is spurred by an audience suggestion. According to Stoltenberg, “The audience plays a huge role in the show. We’re always asking ourselves what’s going to connect with them.”

Like Skinner, Belushi and Stoltenberg want to take their format in unanticipated directions. “Variety’s really important to us,” Stoltenberg continues. “We like to keep the audience expecting the unexpected. Sometimes it doesn’t work out, but that’s part of the rush and opportunity improv provides. It’s scary and fun. The excitement of getting out on stage keeps you on your toes.”

While the performers can’t help play themselves, the “everyguys” from time to time, they try to change that by transforming into different characters. Once again they’re trying to exceed audience expectations. Since he’s made previous trips here with Dad’s Garage, Stoltenberg feels comfortable trying new things here. “[Theatre 99] has done such a good job of creating a community that respects our style of theater,” he says. “That’s great for us because we want to do new things to keep us moving around. We want to be enjoyable, and we really want to do something with the time we’re given here.”

COMEDY FESTIVAL Sketch as Catch Can

by Nick Smith January 18, 2006

Local Sketch Night

Wed. Jan. 18, 9 p.m.

Theatre 99

280 Meeting St

$8

In a festival chock full of improv and even some stand-up, the Local Sketch Night provides a chance to see some prime comedy that performers have actually had a chance to think about before they go on stage. With some of the scripted scenes running up to eight or 10 minutes, there’s time to develop a plot, establish characters, and build up to a climactic musical number or two.